One of my favorite books by Henry James is The American Scene (1907), based on his travels through the eastern United States in 1904 and 1905. I’ll explain below the reasons why I like this overlooked work so much.

James had been away from the United States for 20 years, living in England and traveling in Europe and writing most of the novels and stories that are the basis of his enduring fame. But now, in the early 1900s, he began to feel a need to visit the country of his birth, which had never, at any rate, ceased to be in his thoughts or to nourish his imagination.

His family and friends urged him not to go; he would be appalled by the changes that were taking place, they told him. No more the Jeffersonian nation of small farms and independent businesses, selling to local markets; no more the heroic idealism of abolitionism, or the misty fruitfulness of transcendentalism, or the tragic figure of Lincoln, or the benign presence of Emerson, a family friend.

Instead there was now an industrialized commercialized land presided over not by poets or patriots, but by rich men striving to become richer and to live on as large a scale as possible. It was a land too infatuated with the future to care much for the past, traces of which survived mainly by chance in small eddies alongside the torrent of growth and progress.

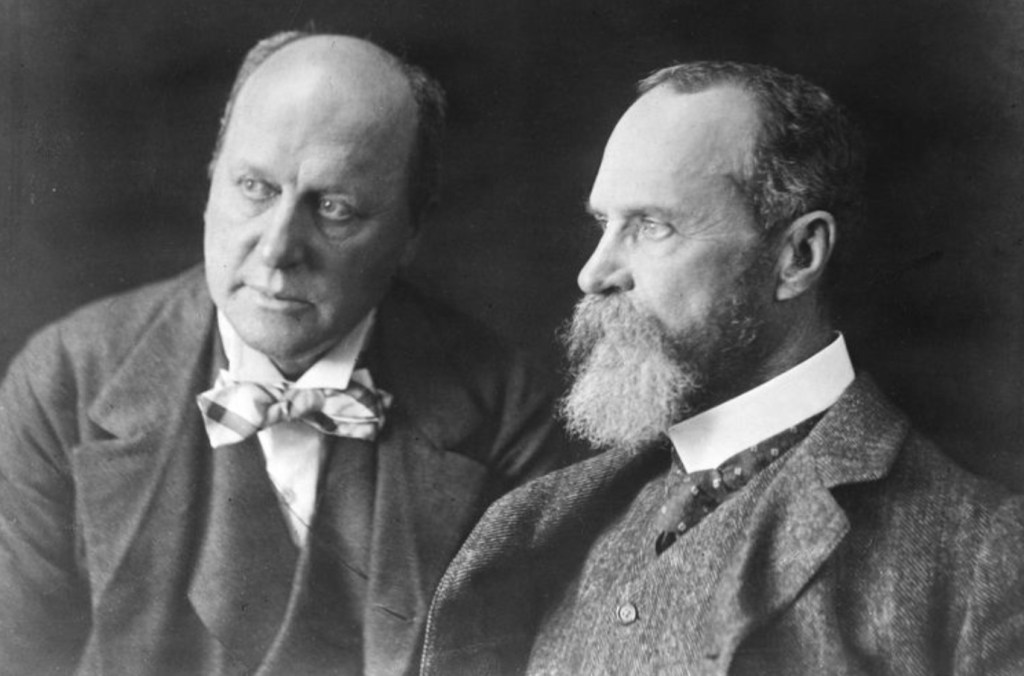

Henry (left) and William James, at William’s house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1904

He planned to visit all parts of the country, and succeeded; but back in England he had so many writing projects to start or finish that he was able only to write about New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and the south.

The grounds of my enjoyment of The American Scene are partly literary. The American Scene is written in a complex style often referred to as “late James” in contrast with the simpler style of his earlier novels and stories. Subordination, qualification, restatement, and refinement are basic features of this later style. It asks readers to read it slowly and then to read it slowly once more, to worry out of it the subtle perceptions and precise distinctions with which it is loaded. The critic Irving Howe says that no more than two or three pages of The American Scene should be read at a sitting. I’ve found that to be about right.

And I love this language, even if I have to read some passages over and over again to understand them. (I majored in classics, after all.) Reading it this way, I become reacquainted with the rich harmonies of English, with its prodigious vocabulary and oratorical power. To read such prose is refreshment after constant exposure to the castrated English in which even serious novels are written today.

But I also like The American Scene on non-literary grounds. James was a dismayed lover of the country of his birth, and so am I. It was Henry’s brother William who complained about their country’s devotion to “the bitch goddess success.” Henry saw changes brought about by that devotion everywhere as soon as he disembarked from his ship at Hoboken (to be the setting fifty years later of the movie On the Waterfront). He saw rows of expensive mansions along the Jersey shore, built to proclaim their extreme expensiveness but hapless to do anything else. In the headlines today we read about parents risking jail to get their children accepted by Ivy League colleges, the ultimate measure of success. James loved his country without in the least idealizing it; that is what I try to do.

The American Scene is about what America is not what it should be. James came chiefly as an observer, not a critic. In a passage about the Bowery, he uses the phrase “swarming jewry” to describe the crowds of jewish immigrants, mostly from eastern Europe, that he saw there filling the streets and the shops and the crowded tenements. The phrase sounds anti-semitic, but James had no desire that jews be excluded from America’s future. He visited their shops and the tenements and attended yiddish theatre. He was fascinated by the yiddish language and expected that it would enter into the making of the language of the future. He had none of the modern anti-semite’s fear of being “replaced”.

James sought to register the impersonal characteristic facts on his awareness for later transfer to his book. Throughout the book, he refers to himself as a “restless analyst” but he never intended to be an analyst of American institutions or mores in the way that Alexis de Tocqueville or James Bryce were. He said that he was “incapable of information.” More importantly for his purposes there are:

features of the human scene, there are properties of the social air, that the newspapers, reports, surveys and blue-books would seem to confess themselves powerlessb to “handle,” and that yet represented to me a greater array of items, a heavier expression of character, than my own pair of scales would ever weigh, keep them as clear for it as I might.

For some, The American Scene will be disappointingly impersonal. So famous a writer as Henry James now was could hardly avoid having to meet and dine with celebrities, and he met and dined with many. His first stop after his arrival at Hoboken was the home of the owner of Harpers, the firm that had agreed to publish the book that he would make out of his travels in America. Mark Twain was already a guest at the owner’s house, and what these two giants of American literature said to each other would be of the greatest interest. But neither the owner nor Mark Twain is mentioned in The American Scene. Neither is there any mention of James’ stay with Edith Wharton and her husband in western Massachusetts, or of the occasion, after dinner there, when James read out loud from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and Out of the Cradles Endlessly Rocking, and When Lilacs Last in the Dootyard Bloomed — read in a sort of subdued ecstasy. For details such as this, there is Leon Edel’s great biography of James.

James was more at home in refined settings such as the home of the gracious Whartons; he knew that he was, and on this trip to America he sought out unfamiliar settings where he knew that his capacity for receiving impressions would be tested.

James was surprised and dismayed by much of what he saw, but in most cases confined himself to recording his impressions. In a few cases, however, he could not contain his contempt, and then he was withering. For example, in New Hampshire he came across the following group of vociferous young people on vacation near North Conway:

The freedoms of the young three who were, by the way, not in their earliest bloom either were thus bandied in the void of the gorgeous valley without even a consciousness of its shriller, its recording echoes. The whole phenomenon was documentary ; it started, for the restless analyst, innumerable questions, amid which he felt himself sink beyond his depth. The immodesty was too colossal to be anything but innocence yet the innocence, on the other hand, was too colossal to be anything but inane. And they were alive, the slightly stale three : they talked, they laughed, they sang, they shrieked, they romped, they scaled the pinnacle of publicity and perched on it flipping their wings ; whereby they were shown in possession of many of the movements of life.

We learn from James’ biographer Leon Edel that he visited his brother William and his family in Chicorua, New Hamphire and took long walks in the hills, marveling at the autumn colors:

The apples are everywhere and every interval, every old clearing, an orchard ; they have ” run down ” from neglect and shrunken from cheapness you pick them up from under your feet but to bite into them, for fellowship, and throw them away ; but as you catch their young brightness in the blue air, where they suggest strings of strange-coloured pearls tangled in the knotted boughs, as you note their manner of swarming for a brief and wasted gaiety, they seem to ask to be praised only by the cheerful shepherd and the oaten pipe.

But amidst the “Arcadian” beauty of the New Hampshire autumn, he found poverty and squalor, and a degradation of the manners of the people suffering this poverty and squalor. Emerson had written “The god who made New Hampshire taunted the lofty land with little men” and James was of the same mind. He speculated that this degradation of manners was owing to the lack of two features of the English and European social landscape, the squire and the parson.

Didn’t it appear at moments a theme for endless study, this queer range of the finer irritability in the breasts of those whose fastidiousness was compatible with the violation of almost every grace in life but that one? “Are you the woman of the house?” a rustic cynically squalid, and who makes it a condition of any intercourse that he be received at the front door of the house, not at the back, asks of a mattresse de maison, a summer person trained to resignation, as preliminary to a message brought, as he then mentions, from the “washerlady.”

In New York City, he was overwhelmed by the presence of “the alien” — the recent immigrants to be found everywhere, but especially on the “electric cars” that James used to get around the city. But James wondered whether the term “alien” had any meaning in this new America:

Which is the American, by these scant measures?—which is not the alien, over a large part of the country at least, and where does one put a finger on the dividing line, or, for that matter, “spot” and identify any particular phase of the conversion, any one of its successive moments?

James wonders at the ease with which immigrants feel accepted in the New World:

The great fact about his companions was that, foreign as they might be, newly inducted as they might be, they were at home, really more at home, at the end of their few weeks or months or their year or two, than they had ever in their lives been before; and that he was at home too, quite with the same intensity: and yet that it was this very equality of condition that, from side to side, made the whole medium so strange.

But he found the new immigrants unapproachable, as if they were wholly engrossed by working out for themselves the import of their new life as Americans. He could not say for himself whether this made them “promising or portentous”.

The pages that James devotes to Boston, Concord, Salem, and the mid-Atlantic states are filled with the same brilliance and originality of perception; and in spite of being 120 years old, these perceptions do not seem to be of a foreign county or a far distant time, but very much of here and today.

He had little to say about the south, except that it still bore the marks of defeat (Appommatox having been a mere forty years before), and, presciently, that hatred of the liberated black was the chief note of society there. He found the blacks demoralized but praised W. E. B. Dubois’ book The Souls of Black Folks as the only book of real distinction to have come out of the South.

Why is The American Scene less read and commented on than most other works by James? It is not the only difficult book that James wrote. It may be that its unpopularity is owing not only in its style, but also to its refusal to be summarized. What James saw in 1904 and 1905 was a rapidly growing country of complexity unexampled on the face of the Earth. It was too large, too marked by contradictions, to be resolved into findings. Instead, “I would take my stand on my gathered impressions, since it was all for them, for them only, that I returned.” The uneasiness pervading those impressions, however, is unmistakeable. Would the people be worthy of the greatness of the land? In his preface to Leaves of Grass, Whitman had written “The largeness of nature or the nation were monstrous without a corresponding largeness and generosity of the spirit of the citizen.” James’ travels in America had left him unsure that there was a corresponding largeness and generosity of the spirit of the citizen.

But he had never ceased to be an American, it was still his native land, and because of the love he felt for it, he paid it the honesty of his gathered impressions.