Everyone knows that people today read less than than their parents and grandparents did; best selling books have been written to deplore this fact. Several groups of people, however, read as much as anyone ever did, because their professions require them to. These are college professors and critics in and out of academe. But according to Robert Alter, a distinguished scholar of Hebrew scripture at the University of California Berkley, many people who are professionally committed to reading no longer believe that literature, whether novels, stories, or poetry, can be a legitimate source of inspiration, knowledge, or pleasure. They see literature either as a mirage without substance, an exercise in solipsism without connection to objective reality, or an inexcusable self-indulgence in a world still tormented by injustice, poverty, and war. In his essay “The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Ideology”, Alter argues that the fate of literature rests with people who will keep on reading it because — of all things — they like it!

I can’t help but believe that I am right in enjoying works like Don Quixote or “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” even in this rotten world, but I also take comfort in the words of critics who believe that the reading of literature is an indispensible part of our enjoyment of life. And my favorite among such critics is George Saintsbury.

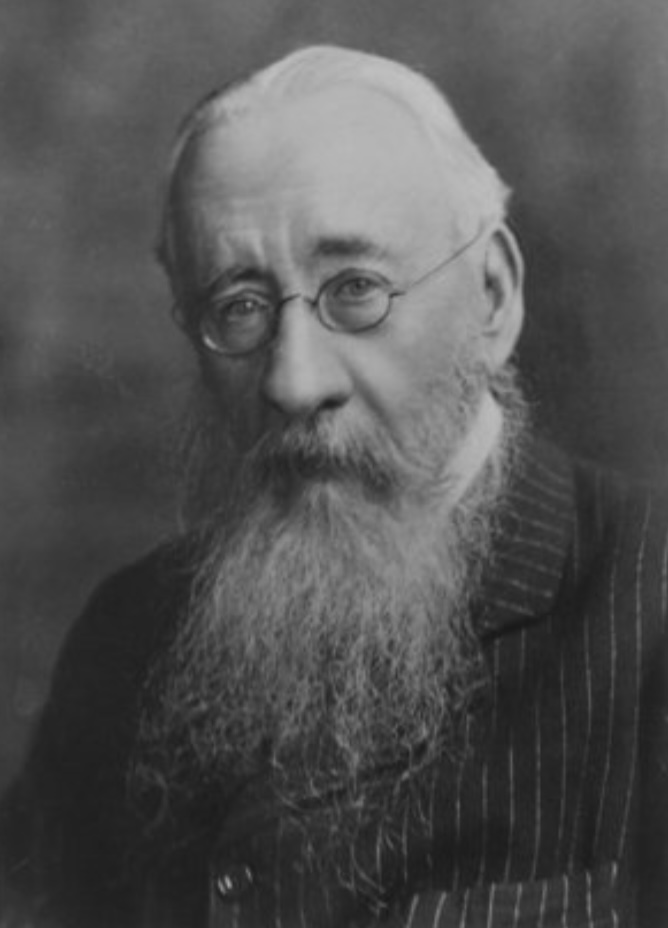

George Saintsbury (1845 – 1933), was a British scholar, university professor, and author of A Short History of French Literature (1882), Specimens of English Prose Style from Malory to Macaulay (1885), A Short History of English Literature (1898), Historical Manual of English Prosody (1910), Notes on a Cellar-Book (1920), and many other learned, authoritative, and readable books on literature and wine.

A recent biographer, Dorothy Richardson Jones, calls Saintsbury the “King of Critics”. I would call him the king of readers because of the astonishing number of writers whose works he knew well. His tastes were truly catholic. Jones wrote that “He loved equally the purest lyrics of Shelley and the complexity of Donne, the richness of Rabelais, the panorama of Scott and medieval romance, and the profound depths of irony in Swift and Ecclesiastes, and always urged upon the reader the joys of minor writers.”

As for his manner of writing about them, I defer to Edmund Wilson, who wrote:

Saintsbury was a connoisseur of wines; he wrote an entertaining book on the subject. And his attitude toward literature, too, was that of the connoisseur. He tastes the authors and tells you about the vintages; he distinguishes the qualities of the various wines. His palate was as fine as could be, and he possessed the great qualification that he knew how to take each book on its own terms without expecting it to be some other book and was thus in a position to appreciate a great variety of kinds of writing.

His greatest enthusiasms were what you might expect; he wrote:

The plays of Shakespeare and the English Bible [the King James Version] are, and will ever be, the twin monuments not merely of their own period, but of the perfection of English, the complete expressions of the literary capacities of the language.

And woe to anyone who tampers with his literary gods! I would quote his excoriation of the “dunces” who tampered with the King James Version to produce the Revised Version, but my copy of the book in which he lays them out, his Short History of English Literature, is up in our attic, I don’t know where.

Needless to say, Saintsbury’s style of criticism has become unfashionable: he proposed no theory of literature or of criticism; he wrote clearly and with obvious enthusiasm; and he believes in the worth of literature. His taste has turned out to be as close to infallible as a critic’s can be; I would praise John Keats more highly than he did, but still, he praised Keats. He never as far as I know mistook a poetaster for a poet, as did a certain Victorian critic who wondered in print whether time will judge the great lyric genius of the age to be John Keats or Dorothea Felicia Hemans.

His book about wines, Notes on a Wine Cellar, is said to be delightful, but I haven’t read it. I gave up drinking when I found that I didn’t read much when I drank. All the more reason to be in awe of Saintsbury, who could still read a vast amount when he drank. I’m drinking coffee as I write this.

Politically, Saintsbury was a reactionary who had contempt for the poor and scorn for governmental attempts to lighten their misery. It would have pained me to read what he would have said about the New Deal, but he died in 1933, too soon to become acquainted with it.

I can think of only one recent critic who had something like Saintsbury’s vast reading and his unsystematic intuitive love of literature: the poet Randall Jarrell. Both of these critics help me see things that I wasn’t seeing on my own. And they prove to me their genuine worth as critics by making me eager to stop reading them and start reading the poems, stories, and plays that they have been writing about with so much knowledge, understanding, and love.