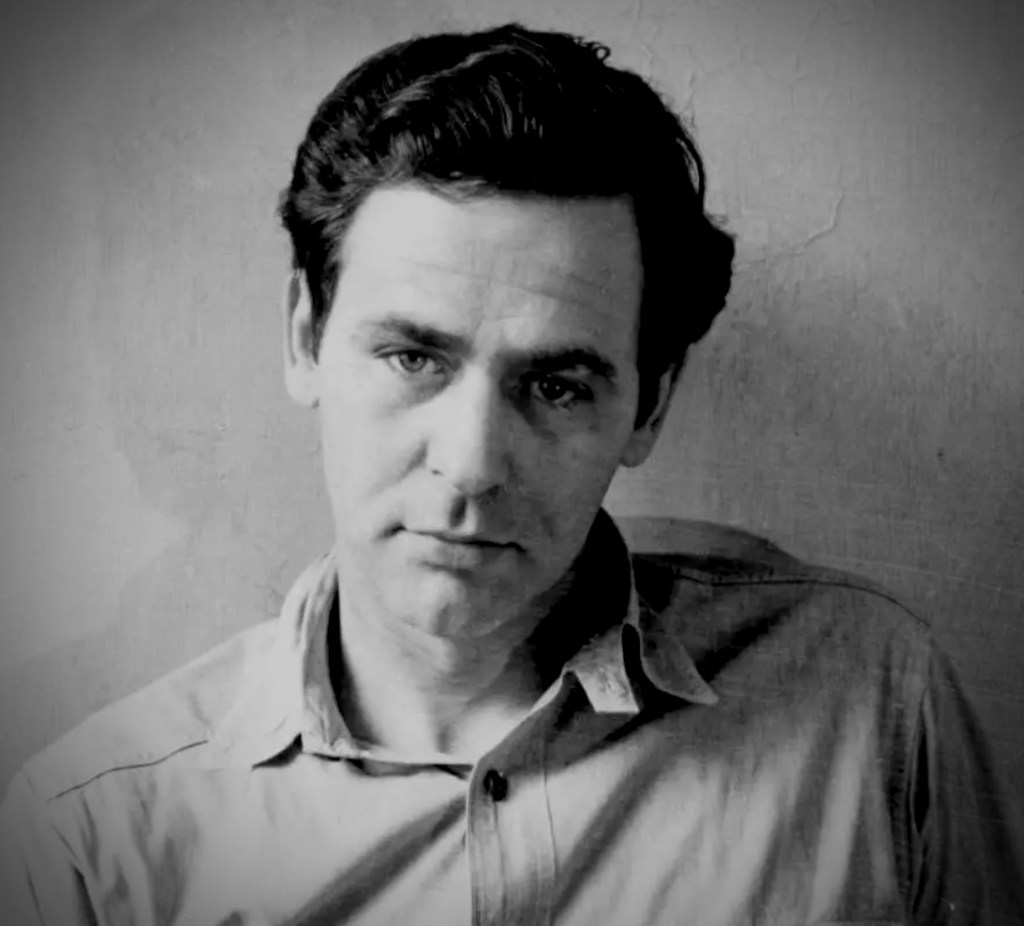

I don’t write about movies on this website, but in this post I write about a book about movies. The book is Agee on Film Volume 1 Reviews and Comment. The author, James Agee (1909 — 1955) , reviewed movies for Time and The Nation. His reviews set a standard for insight and style that in my opinion has never been equalled — Pauline and Roger will forgive me.

(A companion volume to Agee on Film contains the screenplays that Agee wrote for The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter. The Library of America has brought out a volume of Agee’s writings about the movies.)

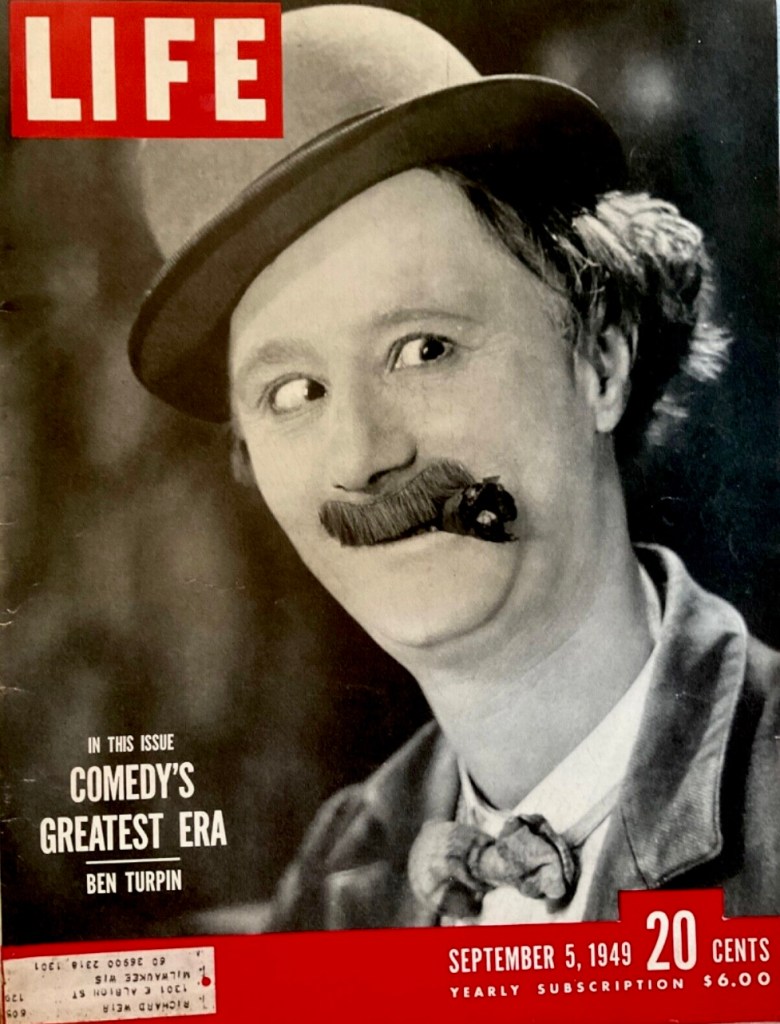

In this post, I will write only about Agee’s famous essay “Comedy’s Greatest Era”, which is included in Agee on Film, Volume 1. This essay originally appeared in the September 5, 1949 issue of Life Magazine. As for the movie reviews reprinted in Agee on Film, Volume 1, promise me that you will read them sometime — preferably soon, for life is uncertain. You don’t want to miss them.

Comedy’s greatest era happened in the brief interval of time between the emergence of technical advances that made the era possible and the emergence of further advances what brought it to a close.

Early in the twentieth century — after decades of technical development — it had become possible at last to create convincing illusions of continuous motion by projecting 16 photographic images per second on a screen. The images were of successive stages of motion; the human brain knit them into a single seamless flow. The illusions, which the public eagerly bought tickets to witness, became known as movies.

The movies were black and white and soundless. They were a perfect medium for a particular visual art which came into existence and achieved classic form almost overnight. That visual art was silent comedy. The silent comedians based their art on the limitations of the medium in which they worked. Silence concentrated the viewers’ attention on motion. Lack of color concentrated their attention on form. The silent comedians exploited the possibilities of motion and form to get the most laughs possible out of tripping over a dog or stepping into an uncovered manhole or being hit in the face with a cream pie.

While audiences were being entertained by silent comedy, the complex technical innovations needed for adding sound to movies were being made with astonishing speed. In 1927, the first movie with sound, The Jazz Singer, was released to the theaters. From now on, the public wanted their movies only with sound. After a few years, that was their only choice; Hollywood was not going to make what the public no longer wanted. The masters of silent comedy either developed the skills needed for acting in movies with sound (a few did) or found other work, or sought oblivion through alcohol or drugs (many did).

Backward-looking movie lovers were not long in realizing that something original and brilliant had been lost when sound was added to movies. But no one was interested in making silent comedies anymore. The masterpieces of silent comedy and the great silent comedians were barely known to the new generation of movie goers.

It was Agee’s essay “Comedy’s Greatest Era” that made later generations aware that silent movies were not crude forerunners of movies with sound, but something excellent and achieved in their own right. The essay received one of the greatest responses in Life magazine’s history, unsurprisingly, for Agee was a brilliant writer, and his love for silent comedy was unfeigned and contagious.

At the beginning of his essay, Agee differentiates the stages of laughter that the best silent comedy elicited from him:

“In the language of screen comedians four of the main grades of laughter are the titter, the yowl, the bellylaugh, and the boffo. The titter is just a titter. The yowl is a runawy titter. Anyone who has ever had the pleasure knows all about a bellylaugh. The boffo is the laugh that kills.

“An ideally good gag, perfectly constructed and played, would bring the victim up this ladder of laughs by cruelly controlled degrees to the top rung, and would then proceed to wobble, shake, wave, and brandish the ladder until he groaned for mercy.”

Agee found much to admire in talking pictures, but they never made him groan for mercy.

Dozens of gifted silent comedians appeared to meet the needs of this new form of popular entertainment. Many were veterans of vaudeville, where they had learned the physical skills that silent comedy depended on. Some of the more notable were, Agee wrote:

“Huge Mack Swain, who looked like a hairy mushroom, rolling his eyes in a manner patented by French Romantics and gasping in some dubious ecstasy. Or Louise Fazenda, the perennial farmer’s daughter and the perfect low-comedy housemaid, primping her spit curl; and how her hair tightened a good-looking face into the incarnation of rampant gullibility. Or snouty James Finlayson, gleefully foreclosing a mortgage, with his look of eternally tasting a spoiled pickle. Or Chester Conklin, a myopic and inebriated little walrus stumbling around in outsize pants. Or Fatty Arbuckle, with his cold eye and his loose, serene smile, his silky manipulation of his bulk and his satanic marksmanship with pies (he was ambidextrous and could simultaneously blind two people in opposite directions).”

But four comedians quickly achieved an eminence in physical humor and expressiveness that the others could only envy: Harry Langdon, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and Charlie Chaplin.

Harry Langdon “looked like an elderly baby and, at times, a baby dope fiend; he could do more with less than any other comedian.”

Harold Lloyd “wore glasses, smiled a great deal and looked like the sort of eager young man who might have quit divinity school to hustle brushes. . . He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth, and out of his thesaurus of smiles he could at a moment’s notice blend prissiness, breeziness and asininity, and still remain tremendously likable. . . . He was especially good at putting a very timid, spoiled or brassy young fellow through devastating embarrassments.”

But Agee devoted the most space in his essay to Keaton and Chaplin, the greatest among the great.

Joseph “Buster” Keaton — the nickname “Buster” was given him by Harry Houdini after watching him fall down a flight of stairs — “ranked almost with Lincoln as an early American archetype; it [his face] was haunting, handsome, almost beautiful, yet it was irreducibly funny; he improved matters by topping it off with a deadly horizontal hat, as flat and thin as a phonograph record. One can never forget Keaton wearing it, standing erect at the prow as his little boat is being launched. The boat goes grandly down the skids and, just as grandly, straight on to the bottom. Keaton never budges. The last you see of him, the water lifts the hat off the stoic head and it floats away.

“No other comedian could do as much with the dead pan. He used this great, sad, motionless face to suggest various related things: a one-track mind near the track’s end of pure insanity; mulish imperturbability under the wildest of circumstances; how dead a human being can get and still be alive; an awe-inspiring sort of patience and power to endure, proper to granite but uncanny in flesh and blood.”

Agee’s admiration for Chaplin was without reserve. He wrote: “Chaplin could probably pantomime Bryce’s The American Commonwealth without ever blurring a syllable and make it paralyzingly funny into the bargain.” Actors who worked with Chaplin have recalled his astonishingly funny pantomiming at lunchtime, lost forever, like the snowman that Michelangelo made for the Medicis.

Agee tries to define what set Chaplin apart from other funny men, even the great Keaton, as follows:

“Of all comedians he worked most deeply and most shrewdly within a realization of what a human being is, and is up against. The Tramp is as centrally representative of humanity, as many-sided and as mysterious, as Hamlet, and it seems unlikely that any dancer or actor can ever have excelled him in eloquence, variety or poignancy of motion. As for pure motion, even if he had never gone on to make his magnificent feature-length comedies, Chaplin would have made his period in movies a great one singlehanded even if he had made nothing except [the silent short films] The Cure, or One A.M.”

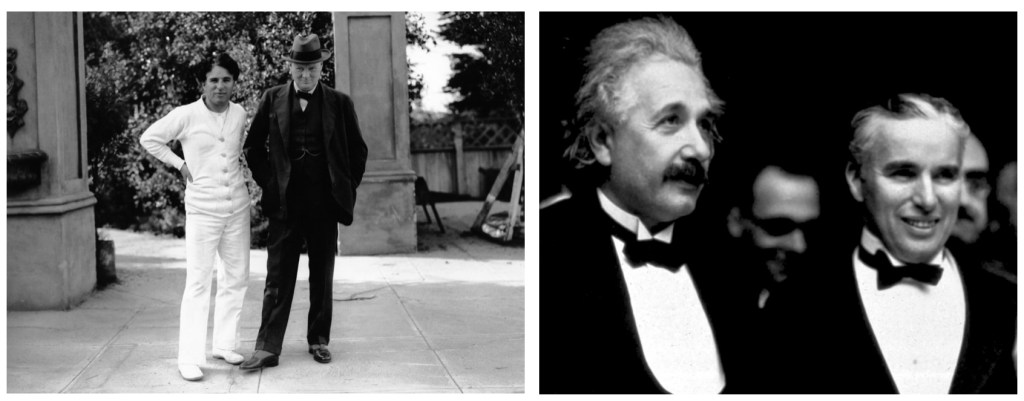

But one of his feature length silent movies, City Lights (1931) must rank as among the greatest movies of any kind ever made — as well as one of the most anticipated while it was being made. The movie loving public was eager to see whether the viruoso of silent comedy could fulfill his genius in the sound era. Winston Churchill, always eager to be where important things were happening, visited Chaplin on the set halfway through the making of the movie. Albert Einstein was Chaplin’s personal guest at the opening.

Right: Albert Einstein attends opening of City Lights as Chaplin’s guest, 1931.

Chaplin’s approach to making his kind of movie in the sound era was compromise. City Lights has a musical sound track, but no spoken dialogue. The closest thing in the sound track to speech is the kazoo like noise that represents the voices of speakers at the dedication of a civic monument — an undisguised dig at the “talkies”.

Comedy’s greatest era, Agee wrote, ended with its greatest moment:

“At the end of City Lights the blind girl who has regained her sight, thanks to the Tramp, sees him for the first time. She has imagined and anticipated him as princely, to say the least; and it has never seriously occurred to him that he is inadequate. She recognizes who he must be by his shy, confident, shining joy as he comes silently toward her. And he recognizes himself, for the first time, through the terrible changes in her face. The camera just exchanges a few quiet close-ups of the emotions which shift and intensify in each face. It is enough to shrivel the heart to see, and it is the greatest piece of acting and the highest moment in movies.”

If technological advance aborted “comedy’s greatest era”, it has preserved many of its greatest moments in digital form, which alone would be enough to keep me from declining into Luddism.