At times I think that my country’s chief claim to have culture is the fact that so many of my fellow Americans are engaged in a war about it. The libraries in public schools are now a chief battle field of that war.

Before I try to account for this war, however, I’d like to state my belief that much of our thinking about almost anything is based on unconscious metaphor. For example, the belief that we can somehow overcome the unimaginable distances of outer space to colonize the planets and the stars is based on our half aware equation of outer space with the American west.

Similarly, the fear that so many parents feel about the contents of the books in the libraries of the schools that their children attend is based on their half aware equation of the ideas in books with viruses — biological or computer. Once let the virus into a child’s brain, they fear, and it will set to work silently to corrupt and pervert the child’s thoughts and imaginations.

It seems to me, though, that this fear is of recent origin. The child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim thought that fear of the human imagination and what it might become is owing to a popular misunderstanding of Freud. Freud taught us — it is commonly thought — that the human imagination is a seething cauldron of semi-conscious impulses that must be restrained and regulated by willed effort. It must be nourished with wholesome materials. Its unwholesome impulses must be rigorously suppressed. This thought is held by people who may never have heard of the Viennese doctor.

Earlier generations were not so afraid of the imagination. Parents otherwise strict in the way they raised their children allowed those same children great freedom in matters of the imagination. In the early nineteenth century, for example, the Ingoldsby Legends were popular and approved reading for English children. These stories were filled with the macabre, the grotesque, the supernatural. One story, for example, was about an upper class married woman who was having a tryst with a younger man. The woman and her lover decided to get rid of the husband and drowned him in a pond. When his body was discovered, it was found to be covered with eels. The ungrieving widow ordered her butler to pull the eels off the body of her husband and cook them for herself and her lover.

”There are delicious!” she exclaimed the widow after tasting the first eel. “Let’s throw him back in and get some more!”

This Edward Goreyesque little tale did not cause a scandal or lead to demands that the The Ingoldsby Legends be banned. It was just make believe, parents reasoned.

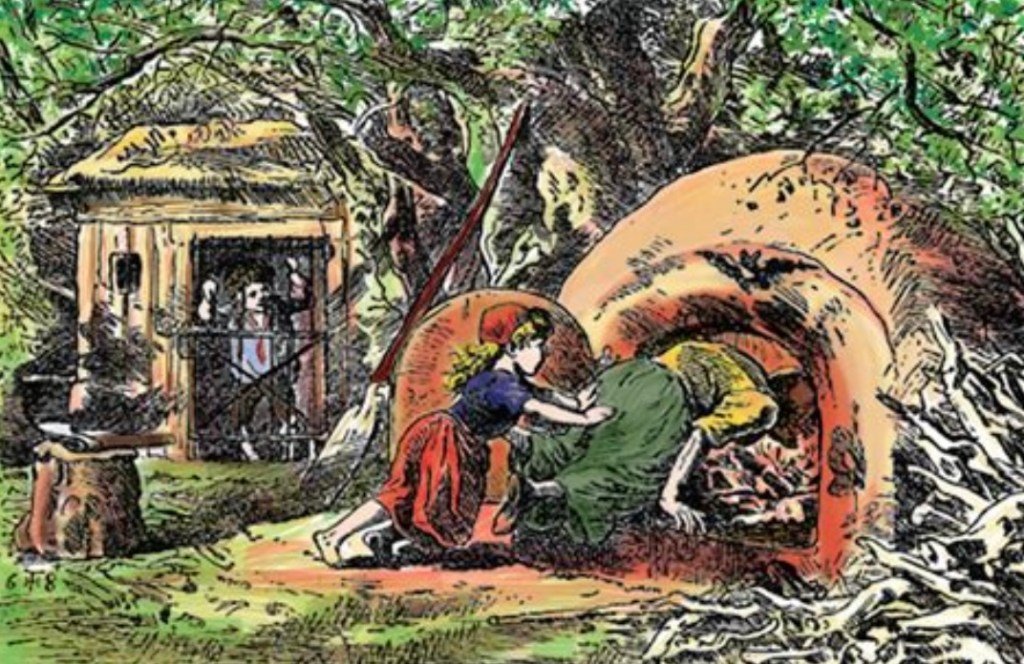

No objections were made to a story about sorcery, kidnapping, child abuse, and cannibalism; a story in which children resolve their conflict with an adult by killing the adult. The story? Hansel and Gretel.

And then there was the young man whose favorite reading was the One Thousand and One Arabian Nights — stories of magic and sorcery steeped in muslim belief and imagery. He wished it were all true, he confessed in his masterpiece, Apologia Pro Vita Sua. The young man was John Henry Cardinal Newman.

Parents who are afraid that their children will want sex change operations if they read books about transexuals live in a world of dangers that are none the less terrifying for being imaginary. Behind their militancy is real anguish. They cannot be argued our of their fears; they are not readers themselves, in many cases, and their fear of books is, literally, a fear of the unknown.

I have my own objection to reading fare that fosters understanding of people who are different from us while offering nothing to nourish the imagination. It is not that it will corrupt the imaginations of young readers but that it will impoverish them. Yes, tolerance and understanding are important qualities and it is part of the job of schools to foster these qualities. But isn’t it a mission of the schools to nourish the imaginations of students, too? Children who have never sailed to Treasure Island with Jack Hawkins and Long John Silver; who have never, with the nurse Evangeline, bent over the form of an dying aged man and recognized, in him, the young man whom she had loved and been parted from many years ago; who never, in reading the classics, come to know “the satisfaction of superior speech” that a high school teacher named Robert Frost once hoped to acquaint his students with — children who miss out on these things are deprived, and there will be no making up for it.

?

A splendid observation — thank you — about the danger of living in a world in which a child is protected from robust imagery in literary works as zealously as from paedophilia; that child would be fiercely literalistic and devoid of complexity, subtlety, or the ability to master fears and problems through a well-developed imagination. Currently, literature in this country is being battered from two directions: from the modern Kulturkampf warriors of the right, and from the offense- and safetyism-obsessed left. The Bettelheim observation, though, about the fear of irreversible mind pollution is really interesting. Could it simply be that as children have become fewer and more expensive (in the expansive sense of the word), that the latest generation of parents have become more fearful of the, well, “spoliation” of their offspring, for lack of a better word?

LikeLike

A new book by Paul Campos, “A Fan’s Life – The Agony of Victory and Thrill of Defeat,” makes an interesting case about sports fan fanaticism. The book claims that the Internet, where sports fan message boards have thrived, gave birth to frenzied fan bases whose attitudes have spilled into out culture and politics. If you ever been on a sports message board, you will see the validity of this idea. Is there much difference between a rabid OSU fan and MAGA supporter?

LikeLike

Thanks. I’ll look that up.

LikeLike