Sometimes, when I am tired of being myself, I read biographies and become the subject of each biography as I read it. Of course fiction can help me escape myself, but that’s different. I don’t like to identify too closely with the characters in fiction. I have no desire to be either Huck or Jim, however wonderful it is to read about their progress down the Mississippi. But when I read biographies, I identify myself with the subject, eagerly. Of course, I read biographies only of people whom I admire.

Here are some great biographies that I have enjoyed. Feel free to mention your own favorites in the comments section at the end of this article.

+++

Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson is of course supreme in this branch of literature. James Boswell (1740 – 1795) was a lawyer from Edinburgh and a rather contemptible person with boundless literary ambitions. Fortunately for literature, Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784) was fond of odd, broken, disreputable people, and permitted Boswell to shadow him for much of the last twenty years of his life. During this time Johnson was able, thanks to a pension from the crown, to live for conversation. He “talked for victory” whenever he met with his drinking companions: David Garrick, Oliver Goldsmith, Edward Gibbon, and Edmund Burke, and others. (Edmund Burke, Johnson confessed, was the only one of his friends whose own powers of conversation inspired in him a degree of fear.)

Boswell’s great gift was for recording Johnson’s conversations with his friends — combative, learned, wise, and down-to-Earth conversation, a flow of opinion from the enormously well stocked mind of a man who had suffered in life most of what there is to suffer, and whose final months, which Boswell was to record, were to be harrowingly painful. It required very great gifts to make a convincing portrait of a man as complex as Johnson, who was both misanthropic and compassionate, and who was both a devout Christian and a tough-minded sceptic. Boswell had the gifts.

[John Gibson Lockhart’s Life of Sir Walter Scott is considered by many critics to be nearly as great a biography as Boswell’s Life of Johnson. I’ve thrown it on my stack.]

+++

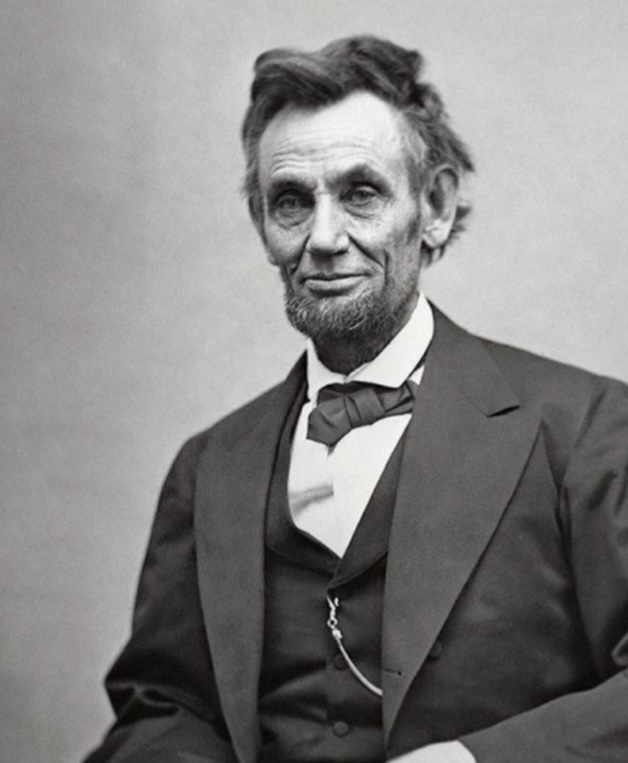

Lord Charnwood’s Abrahan Lincoln (1916) is the best written and most intelligent biography of Lincoln that I know of. Godfrey Rathbone Benson, 1st Baron Charnwood (1864 – 1945) wrote at perhaps the ideal moment for a biographer of Lincoln: long enough after Lincoln’s death that most of the local and temporary controversies surrounding him had subsided, but soon enough after his death that there were still people to talk to who remembered his life and times. One of these people was Charnwood’s friend Henry James, whose family had been passionately attached to the Union cause.

Recent biographies of Lincoln can take advantage of the never ending research into Lincoln’s life; outstanding among these is Michael Burlingame’s amazingly detailed Abraham Lincoln: A Life (2013). But no one had a more sympathetic understanding of America’s representative common man than Baron Charnwood. My opinion, of course.

+++

Henry James, Jr. wrote so much and so well that it is somewhat surprising to learn that he had time apart from his writing for — a life. Leon Edel’s justly esteemed five volume biography shows James to have been a kind and gregarious man who indeed had and loved a life apart from his writing. Any biography of Henry James has also to be a biography of the entire James family, to the great enrichment of the subject, and Edel manages to include the immensely gifted family without losing sight of his principal subject. Somewhat scanted is the question of James’ sexuality, and this is fine with me, because I cannot see how having a certain answer to this question could in any way increase my understanding or enjoyment of his writing.

James’ life is of interest to us because of what he wrote, and Edel had to find a way to incorporate discussion of his writings into the narrative of his life. I never felt in reading the biography that the discussion of his works was ever an intrusion into his life’s story, or that the discussion of the works was scanted to return to the life. I never felt, in reading this biography, that I was reading gossip, no doubt because Edel maintained his respect for James’ life even as he investigated it. In the end, James appears as a heroic character who worked steadily toward the same goal all his life, which was to elevate the English novel to the same aesthetic level with the west’s greatest music and painting. He died in the assurance that he had succeeded, and it is my paltry opinion that he was right.

+++

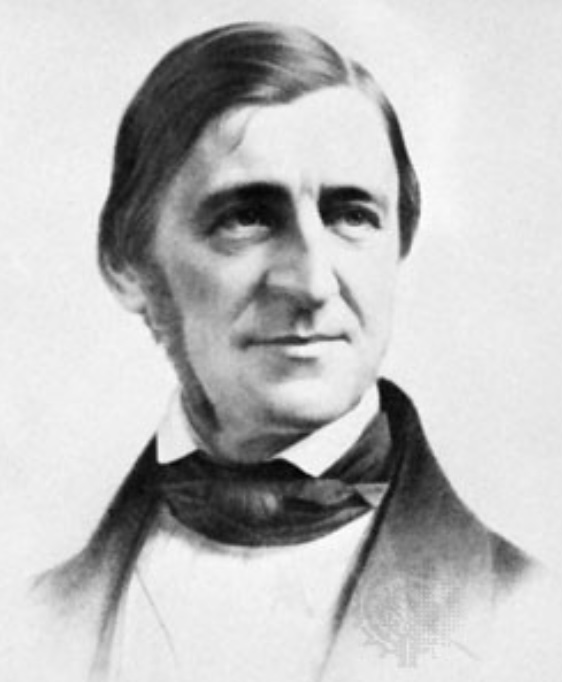

I recently had a minor medical procedure performed on me at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Massachusetts. I took along with me a copy of Emerson’s first book, Nature, to read in the waiting room. When I showed it to my doctor, he said, “I see, that’s funny. Your man there has the same name as this hospital.”

No, Ralph Waldo Emerson isn’t as well known today as he was in his lifetime, and he is less well known than his mentee and friend Henry David Thoreau.

But both men received something close to the attention they deserve in intellectual biographies by Robert Richardson. Richardson’s preparation for writing his books was the same: to read everything that his subject is known to have read. His subjects being great readers, Richardson needed about ten years to prepare to write each book.

Henry David Thoreau: A Life of the Mind (1986) reveals Thoreau to have been a scholar, something you might have guessed from reading Jeffrey Cramer’s wonderful annotated editions of his works. At Harvard, he read widely in Latin, Greek, French, Anglo Saxon, and middle and old English. After college, he studied German with Orestes Brownson, and began to read Goethe’s Italiensche Reise (Italian Travel Journals) in the original. He also translated Aeschylus’ play Prometheus Bound. (One of Aeschylus’s easier plays, which isn’t saying much.) And he continued his loving study of Homer’s Iliad and Vergil’s Georgics. Thoreau’s love of the Latin and Greek classics — he devoted a chapter of Walden to a defense of reading them in the original — set him somewhat apart from the other members of the transcendentalist set, who were in love with the German romantic writers. Thoreau’s classicism may account for his superior grasp of the demands of form that he displayed in Walden, certainly a more written book than anything that Emerson was producing.

Thoreau’s interests, as Richardson showed, were wide ranging and changed constantly throughout his rather short life. One of his convictions was constant, however. The lives of men and women were greatly impoverished for being estranged from nature.

Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Mind on Fire is more likely to change a reader’s idea of its subject that Richardson’s book on Thoreau. Thoreau was in fact somewhat like the popular conception of him — a rugged outdoor type. But Emerson is shown by Richardson not to have been the etherial type lost in contemplation of his oversoul that he is taken for. He too was rugged, outdoorsy, athletic. He was attached to the common joys of life, had a gift for friendship and an enormous love of family. [Personal note: I once worked as a technical writer in the same department as a great granddaughter of Emerson and am happy to be able to report that she was friendly, kind, and immensely likeable.)

Emerson was, like Thoreau, enormously well 8read, although he preferred to read foreign literature in English translation. He was hospitable to ideas from all sources, although he had one great idea to which he returned again and again all his life: that the human mind was not a tabula rasa but was brimming with a native fund of ideas — thus taking his stand with Kant against Hume. Emerson may have been on fire with ideas but he was passionately attached to the homely goodness of the world. It was no accident that his greatest disciple should be Walt Whitman, the connoisseur of leaves of grass.

I’ve never been a big one for biographies, and I’m still not sure why, though I’ve read a few fine ones. I’ve read excerpts of Boswell’s Johnson and they were engaging and well-written. My favorite biography, I think, is Frederick Douglass’s autobiography (I read the first one), which was taut, a stylistic gem, and a masterpiece of anti-slavery literature. And this reminds me that I’d like to read U.S. Grant’s autobiography because, again, its subject is meaningful and it’s stylistically great (I simply don’t know how much credit to assign to Mark Twain for that).

LikeLike

I think Grant can take credit for the style of his memoirs. The clarity of his written messages to subordinates was well known.

LikeLike

Good one, thanks

LikeLike

Peter, You might like the bio of Thoreau.

LikeLike

The Essays of Henry David Thoreau edited by Lewis Hyde is a great collection

LikeLike

I read the intro, which was good. The library of America has published all of Thoreau’s essays and miscellaneous writings in a single volume. Wonderful stuff.

LikeLike

John.

<

div>These reviews read like a labor of love. You whet my appetite to revisit each subject, which will doub

LikeLike

Nothing would please me more than to know that I’d put you on to a good book. The biography of Emerson is especially good. And someone needs to publish a selection of the writings of Emerson’s aunt Mary Moody Emerson — she was an impressive scholar, thinker, and writer. Emerson revered her.

LikeLike