Note: This post replaces one on the same subject that I published earlier.

O GODDESS! sing the wrath of Peleus' son, Achilles; sing the deadly wrath that brought Woes numberless upon the Greeks, and swept To Hades many a valiant soul, and gave Their limbs a prey to dogs and birds of air, — For so had Jove appointed, — from the time When the two chiefs, Atrides, king of men. And great Achilles, parted first as foes. The Iliad, Book 1, lines 1 - 8, trans. William Cullen Bryant

In this essay I try to explain why, fifty years after I first read the Iliad, I keep returning to it, and why I think that others might want to read it, too..

I also try to explain how I overcame the obstacles that I encountered in getting to know the Iliad well enough to read it with enjoyment — something that I hope may be of interest to others who are thinking about reading the Iliad, or who have tried to read it only to be discouraged on first encounter by the poem’s great length, seemingly sprawling and formless and monotonously given over to the graphic description of the slaughter of warrior by warrior.

I write about several well known English translations of the Iliad, and why I prefer some to others.

And I write for those who suspect that the Iliad is getting a pass for being so old, for having been so long honored, for being, in short, a Big Name. Where so many have been digging for so long, there has to be gold. I have found gold, and in this essay I will try to illustrate with excerpts from the poem what that gold is like for me. In the meanwhile, I will let William Cullen Bryant speak for me, since his thoughts now represent my own:

[The Iliad is ] a work of an inexhaustible imagination, with characters vigorously drawn and finely discriminated, and incidents rapidly succeeding each other and infinitely diversified, — everywhere a noble simplicity, mellifluous numbers, and images of beauty and grandeur . . .

This essay is not a work of scholarship but an account of my experience as a reader of the Iliad. For scholarship, please see the section titled Some Books that Have Helped Me at the end of this post.

Note: All excerpts from the Iliad that appear below are taken from the 1871 translation by William Cullen Bryant.

What I Needed to Know First

The story that Homer tells in the Iliad was familiar to his audiences from beginning to end. But I was not as familiar with the story as I needed to be in order to read the Iliad with understanding and enjoyment. I had homework to do. I consulted handbooks of mythology. Rosemary Sutcliff’s book “Black Ships Before Troy” is an excellent retelling of the Iliad for young adults that includes the poem’s background in mythology. Robert Graves’ “Greek Gods and Heroes” is also useful. Today, synopses of the Iliad and lists of the principle characters are easily found online.

At the very least, I needed to be familiar with these parts of the mythological background of the Iliad:

- The birth of Helen and her brothers, Castor and Pollux.

- The marriage of Helen with Menelaus, King Sparta.

- The marriage of the sea goddess Thetis with Peleus, King of the Myrmidons.

- The birth of Achilles, son of Peleus and Thetis, and the prophesy relating to his glorious life and early death.

- The award of the golden apple, inscribed ‘’to the fairest’’, to Aphrodite by Paris, Prince of Troy, thus turning the goddesses not judged to be the fairest, Hera and Athena, into unappeasable enemies of Troy.

- The elopement of Helen with Paris.

- The Kings of Greece, true to their mutual oaths, go to war against Troy to bring Helen home to Sparta.

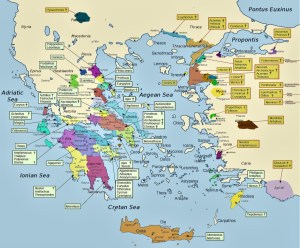

I also found it helpful to print a map showing where all the contingents of Greeks and of Trojans mentioned in the “Catalog of Ships” (Book Two) come from, and who their leaders are. I found the map below by searching online for “catalog of ships map”. I had my print laminated, and I keep it handy when I am reading the Iliad.

Why I Read the Iliad

In spite of the labour and the difficulty it is this that draws us back and back to the Greeks; the stable, the permanent, the original human being is to be found there.

Virginia Woolf, ‘’On Not Knowing Greek’

The Iliad begins with an explosion of anger and ends on a note of fear, grief, and exhaustion. Between its beginning and end is a vast tableau of slaughter as warriors seek transitory earthly glory by killing other warriors. Why read something like that? Aren’t the day’s headlines appalling enough?

I have read and enjoyed the Iliad for different reasons at different times in my life.

I first read it because it was a story about heroes. In modern usage, the term “hero” refers to a person who does something extraordinary and praiseworthy; for example, a man or woman who rescues someone trapped in a burning building. But my interest was in heroes of an older traditional sort: men of some former time who were bigger, stronger, and more courageous than men of today. Such heroes walked among the gods and some were even offsprings of the gods. In this traditional sense, the term “hero” refers to something that a man is.

Stories about heroes in this older sense are thought to be very old indeed — as old as campfires and story telling. Their appeal, then, is to something basic in our nature, and if today’s serious literature is preoccupied with the unheroic side of men and women, stories about heroes still flourish in comic books and video games and movies. This latter fact may make it hard for some readers to enjoy stories about heroes, their appeal being to our primitive (i. e. lowbrow) side. But I’ve found that to understand and enjoy the Iliad, I have had to understand as best I can the appeal of this human writ large, the hero.

I have also developed a newer interest in the Iliad, now that I have achieved my biblically allotted three score years and ten (and a little more). I am suddenly conscious of not having much time left for reading or anything else. For this reason I am losing interest in life’s temporary, local, accidental features. I’m not interested in novels that depict, say, all the local good and local bad in lower middle class life in a certain village in Victorian England or anywhere else. I want a summing up of universal facts, an abstraction from life of its essence. “Nothing can please many, and please long, but just representations of general nature,” wrote Samuel Johnson in the preface to his edition of Shakespeare. The Iliad abounds in just representations of a general nature — representations of men and women, the young and the old, mortal and divine, all caught up in a terrible and apparently endless war. “The poems of Homer,” Johnson continues, “we yet know not to transcend the common limits of human intelligence, but by remarking, that nation after nation, and century after century, has been able to do little more than transpose his incidents, new name his characters, and paraphrase his sentiments.” And this is so because Homer reaches down to the unlocalized general truth about humanity. It is all here: love, hatred, pride, fear, courage, devotion, and just about any other human quality you can think of, distilled into an essence.

However, the just representations of a general nature in the Iliad are found in the context of a warrior culture that is unique and peculiar to its time. Hector prays for his son that some day he may delight his mother by returning from battle carrying the armor of an enemy whom he has slain. Details like this force me to decide how well I want to participate, imaginatively, in a culture in which a mother would be delighted by such bloody trophies. This culture will always remain something exotic to me and unassimilated by my imagination. I have had to learn to accept, rather than enter into, certain elements of the Iliad.

On the whole, I find the Iliad, for all its savage strangeness, easier to accept on its own terms than the Aeneid, Vergil’s Latin epic that was modeled on, and written in competition with, the Iliad. The Aeneid celebrates the origin of the Roman people, the greatness of Rome, and the rule of the emperor Augustus. I enjoy the brilliance of Vergil’s poetry and the unforgettable pathos of many of his episodes, but I find it difficult to enter into his feelings for Rome. The Iliad presents fewer such difficulties. Homer’s evocation of the tragic essence of human existence is true to today’s headlines.

The People of the Iliad

Homer wasn’t a novelist and the Iliad isn’t a novel. An epic poem has its own conventions and requirements. But Homer had a great novelist’s ability to give life to characters with very few words.

The Iliad is about people — people in relation to each other and to a terrible war that is threatening to devour everyone and everything that has attached them to life. Homer portrays people with vividness, subtlety, and economy. (He portrays gods and goddesses with equal skill, but I find them less interesting than mortals because they have so much less at stake.)

I was surprised to learn from Jasper Griffin’s book Homer on Life and Death that some modern scholars have denied that Achilles, Hector, Agamemnon and all the rest are characterized at all. This view makes all the characters in the Iliad to be no more than functional parts of the story. Maybe I am reading the Iliad in a naive and unsophisticated way, but I feel that if Achilles, for example, isn’t characterized — that is, if he isn’t, for the reader, an autonomous being who does and says what he does because his nature requires it — then there are no characters either in the plays of Shakespeare or in the novels of Mark Twain.

I believe that some readers find that Homer fails to characterize the personae of his poem because he does not endow any of them with personal eccentricities. Nestor, an aged leader among the Greeks, is garrulous, but he is not garrulous in the same way as Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield, whose speech can only be called Micawberesque. Nestor’s garrulousness is the garrulousness of all old men who have been relegated to the sidelines by age and who can console themselves only by recalling the great things that they saw, did, and suffered in their youth.

We know, for example, that Helen is filled with remorse and self-loathing as being the cause of the war. Would she be characterized any better if Homer also told us that she bites her nails? Robert Frost said that in art, a little bit of anything goes a long way. Homer’s people are characterized just enough to be real seeming, and no more.

The most important people of the Iliad are: Priam, king of Troy; Hector, a son of Priam, and the greatest Trojan warrior; Achilles, leader of the Greek forces from Phthia, and the greatest warrior on either side; Agamemnon, leader of the Greek forces against Troy; Menelaus, brother of Agamemnon and the husband of Helen; Paris, a son of Priam who ran off with Helen, causing the war; Helen, as beautiful as a goddess and full of self-loathing for being the cause of so much suffering and death; and Odysseus, the cleverest man in either army.

I’m going to limit my discussion of these characters to the three who are central to the action of the poem and whose stories have interested and moved me most vividly: Achilles, Hector, and Helen.

Achilles

Achilles is the embodiment, in a pure concentrated form, of wrath (menin). It is Achilles’ wrath that the poet asks the “goddess” to sing about. It is Achilles’ wrath that sets the action of the Iliad in motion and it is only when his wrath is momentarily appeased that the action can be concluded.

Alexander Pope remarks in the introduction to his translation of the Iliad that no poet since Homer has ever chosen as “simple and single” a theme for a poem as Homer did, in choosing wrath.

Achilles is the merciless man of wrath who nurses his grievances, is dismissive of the suffering of others, and finds it impossible to ignore or forgive slights to his own dignity. (He is alive and among us today, in various incarnations but always easily recognizable.)

I don’t like him, and that is a sign that Homer has made him vivid enough for me that I start to mistake him for a real person. When I read Homer, I find myself on a boundary between art and real life. For Homer’s audiences, however, there would have been no such questions about artistic representation and reality because they regarded Achilles and the other warriors as historical figures.

Achilles possesses to an outstanding degree all the qualities of a great warrior: he is taller and bigger than ordinary men, and stronger; he can run faster and throw a javelin farther. He is semi-divine, his mother being the sea nymph Thetis, and he was trained in the arts of war by a centaur.

Even so, he is doomed. An oracle has declared that he must choose between a long life without glory, or a glorious but short life. He chooses the latter, as any warrior would — as the greatest warrior must. Achilles’ coming death overshadows the whole poem.

Achilles so far has a claim on our pity. But he repels pity by being himself pitiless. He has no pity, first of all, on the other Greeks, who are suffering terrible losses in battle while he sulks in his tent. Agamemnon sends him gifts to soften his anger and to persuade him to return to the war. Achilles rejects the offer:

I hate his gifts; I hold In utter scorn the giver. Were his gifts Tenfold, — nay, twenty-fold, — the worth of all That he possesses, and with added wealth From others, — all the riches that flow in Upon Orchomenus, or Thebes, the pride of Egypt, where large treasures are laid up And through whose hundred gates rush men and steeds. Two hundred through each gate; — nay, should he give As many gifts as there are sands and dust Of earth, — not even then shall Atreus’ son Persuade me, till I reap a just revenge For his foul contumelies.

Achilles’ anger is excessive even by the standards of the warrior culture that formed him. Yes, Agamemnon treated hm with contempt, but the gifts that the Greeks offer him are more than enough to atone for the insult he suffered. Still, he will not be appeased. Achilles does not return to battle until his beloved companion Patroclus is killed in battle by Hector; and then Achilles fights only for a personal reason: to get revenge for the killing of Patroclus by killing Hector.

He is pitiless toward Lycaon, a son of Priam and half brother of Hector. He had ransomed Lycaon once before, and now encounters him for a second time; in the interval, Patroclus has been killed by Hector:

The illustrious son of Priam ended here His prayer, and heard a merciless reply:— “Fool! Never talk of ransom—not a word. Before the evil day on which my friend Was slain, it pleased me oftentimes to spare The Trojans. Many a one I took alive And sold; but now no man of all their race, Whom any god may bring within my reach, Shall leave the field alive, and least of all The sons of Priam. Die thou, then; and why Shouldst thou, my friend, lament? Patroclus died, And greatly he excelled thee. Seest thou not How eminent in stature and in form Am I, whom to a prince renowned for worth A goddess mother bore; yet will there come To me a violent death at morn, at eve, Or at the midday hour, whenever he Whose weapon is to take my life shall cast The spear or send an arrow from the string.” He spake: the Trojan’s heart and knees grew faint; His hand let go the spear; he sat and cowered With outstretched arms. Achilles drew his sword, And smote his neck just at the collar-bone; The two-edged blade was buried deep. He fell Prone on the earth; the black blood spouted forth And steeped the soil. Achilles by the foot Flung him to float among the river-waves, And uttered, boastfully, these wingèd words:— “Lie there among the fishes, who shall feed Upon thy blood unscared. No mother there Shall weep thee lying on thy bier; thy corpse Scamander shall bear down to the broad sea, Where, as he sees thee darkening its face, Some fish shall hasten, darting through the waves, To feed upon Lycaon’s fair white limbs. So perish ye, till sacred Troy be ours, You fleeing, while I follow close and slay. This river cannot aid you—this fair stream With silver eddies, to whose deity Ye offer many beeves in sacrifice, And fling into its gulfs your firm-paced steeds; But thus ye all shall perish, till I take Full vengeance for Patroclus of the Greeks, Whom, while I stood aloof from war, ye slew.”

Achilles’ hatred has made him a lion.

Priam knows this and takes it into account when, as related in the twenty-fourth and final book of the Iliad, he comes to Achilles’ tent to ransom the body of his son Hector. Priam comes to Achilles under the protection of the god Hermes; even so, he must make his request with the greatest possible caution.

He knows that if he asks Achilles to pity him, the father of that very Hector who killed Patroclus, Achilles will be outraged; so, falling on his knees before Achilles, he asks him to think of his own aged father, in far off Phthia. Achilles weeps at the thought of his father and, in the closest approach to empathy that he will ever make, acknowledges that sorrow is the lot of all men.

Priam, encouraged by Achilles’ apparent softening, fearfully asks him to accept a ransom for the body of Hector. Achilles frowns and says:

Anger me not, old man; ’twas in my thought

To let thee ransom Hector. To my tent

The mother came who bore me, sent from Jove,

The daughter of the Ancient of the Sea,

And I perceive, nor can it be concealed,

O Priam, that some god hath guided thee

To our swift galleys; for no mortal man,

Though in his prime of youthful strength, would dare

To come into the camp; he could not pass

The guard, nor move the beams that bar our gates.

So then remind me of my griefs no more,

Lest, suppliant as thou art, I leave thee not

aUnharmed, and thus transgress the laws of Jove.

Achilles tells Priam to stay with him until the morning, when a god will escort him back to Troy in safety. Priam, however, fears that Achilles might suddenly remember Patroclus and become enraged, and returns to Troy with his son’s body during the night, when Achilles and the Greeks are sleeping.

Achilles’ wrath not only results in the deaths of many of his fellow Greeks, who go into battle without his support. It also results in the destruction of Troy, for Achilles’s wrath leads him to seek out and kill Hector. Hector is Troy’s main defense in the war, and his death guarantees Troy’s eventual destruction — a destruction not related in the Iliad. It is this latter far reaching consequence of Achilles’ wrath that provides the title of Homer’s great poem — not the Achillead, but the Iliad (Ilium being another name for Troy).

Hector

Hector, a son of Priam and the greatest Trojan warrior, is a sympathetic character. I like him, once again mistaking one of Homer’s creations for a real person.

Achilles may complain more than Hector complains, but it is Hector who has the most to lose. In her essay “On the Iliad”, Rachel Bespaloff describes Hector as “the guardian of the perishable joys”. Upon him depend a wife, a child, aged parents, brothers and sisters, and all of Troy. He is aware of all that depends on him and is tormented by what will happen to his wife and child if Troy should fall. Meeting his wife and son on the top of the Scaean gate, where they have been watching the battle, Hector says to his wife:

Yet well in my undoubting mind I know

The day shall come in which our sacred Troy,

And Priam, and the people over whom

Spear-bearing Priam rules, shall perish all.

But not the sorrows of the Trojan race,

Nor those of Hecuba herself, nor those

Of royal Priam, iLnor the woes that wait

My brothers many and brave—who all at last,

Slain by the pitiless foe, shall lie in dust—

Grieve me so much as thine, when some mailed Greek

Shall lead thee weeping hence, and take from thee

Thy day of freedom. Thou in Argos then

Shalt at another’s bidding, ply the loom,

And from the fountain of Messeis draw

Water, or from the Hypereian spring,

Constrained unwilling by thy cruel lot.

But he is, like other Homeric warriors, filled with desire for glory, and for the sake of glory he takes risks that horrify those who love and depend on him.

And he makes mistakes. When Achilles withdraws from the war, Hector proposes an all out attack on the Greeks, against the advice of all others. The attack is a disaster for the Trojans, and Hector is to blame.

When Achilles comes to the walls of Troy seeking Hector, Hector knows that he can no longer evade what will be the final test of himself as a warrior. He tries to face Achilles but then, terrified, flees before him. The gods intervene to make him stop, turn, and await Achilles’ fatal assault. His last experience in life is pure terror.

Hector receives the funeral rites that will enable his ghost to repose in the almost nothingness of the afterlife, rather than restlessly seek the funeral honors that have been denied it. The Iliad ends with the words “such were the funeral rites of Hector, breaker of horses.”

Some say that the traditional epithet for Hector, “breaker of horses”, is irrelevant in this context and for that reason is jarring. Some translations of this line, including Bryant’s, omit this epithet altogether. We cannot know whether Homer’s audiences found it irrelevant or jarring. I can only say that it heightens the pathos of Hector’s death for me. It conjures up the unique individual who now has lost all uniqueness and individuality in the blankness of death. The last line of the Iliad is for me the most moving.

Helen

Helen passes her days knowing that she is hated by most of the Trojans as the cause of the war with the Greeks. She judges herself as harshly as they do, and yet (Homer assumes that his audience knew this) she isn’t really to blame for the war.

Protected though she is by Aphrodite, Helen is as vulnerable to loss and grief as anyone else. Sometimes in the telling Homer mingles her loss with irony. When Menelaus and Paris prepare to decide the issue of the war in single combat, Priam, observing the opposed armies from the top of the walls of Troy, asks Helen to point out for him the leading warriors of the Greeks:

Helen, the beautiful and richly-robed, Answered: “Thou seest the mighty Ajax there, The bulwark of the Greeks. On the other side, Among his Cretans, stands Idomeneus, Of godlike aspect, near to whom are grouped The leaders of the Cretans. Oftentimes The warlike Menelaus welcomed him Within our palace, when he came from Crete. I could point out and name the other chiefsO Of the dark-eyed Achaians. Two alone, Princes among their people, are not seen— Castor the fearless horseman, and the skilled In boxing, Pollux—twins; one mother bore Both them and me. Came they not with the rest From pleasant Lacedaemon to the war? Or, having crossed the deep in their good ships, Shun they to fight among the valiant ones Of Greece, because of my reproach and shame?”

She spake; but they already lay in earth In Lacedaemon, their dear native land.

Helen must keep to herself her feelings of self loathing and shame, for she is surrounded by people who would not receive her confessions sympathetically. It is only to Hector, who has always treated her with kindness, that she can speak frankly:

Brother-in-law—for such thou art, though I Am lost to shame, and cause of many ills— Would that some violent blast when I was born Had whirled me to the mountain wilds, or waves Of the hoarse sea, that they might swallow me, Ere deeds like these were done! But since the gods Have thus decreed, why was I not the wife Of one who bears a braver heart and feels Keenly the anger and reproach of men? For Paris hath not, and will never have, A resolute mind, and must abide the effect Of his own folly. Enter thou meanwhile, My brother; seat thee here, for heavily Must press on thee the labors thou dost bear For one so vile as I, and for the sake Of guilty Paris. An unhappy lot, By Jupiter’s appointment, waits us both— A theme of song for men in time to come.

At Hector’s funeral, Helen mourned him as her friend and protector.

The Gods in the Iliad

When I first read the Iliad, I was astute enough to realize that the gods of Olympus are nothing like the God of the great monotheistic religions Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. They behave with great dignity on some occasions and on other occasions they’re 8quarrel among themselves like spoiled children.

Another difference from the deity of the monotheistic religions: they seem to be in a purely transactional relationship with their worshippers. They are, in fact, part of the same honor culture that Homer’s warriors are part of. They demand, as a mark of respect, that mortals make frequent costly sacrifices on their altars. In return, they will grant certain favors to the mortal who keeps their altars smoking with sacrifice. In the last book of the Iliad, the Olympian gods decide to allow Priam to ransom Hector’s body from Achilles in order to give it a proper burial; it was Hector’s due, since he had always sacrificed to them regularly.

Nothing could be more alien to the spirit of Homeric religion than the words of Psalm 51:

For thou desirest not sacrifice; else would I give it: thou delightest not in burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.

The Olympians are angered by a mortal’s tokens of disrespect toward them but do not care whether a mortal’s heart is broken or contrite or anything else.

The gods’ chief function in the Iliad is to emphasize, by way of contrast, the desperate nature of human existence. The gods and goddesses of Olympus have their petty concerns and resentments; they can even, like Aphrodite, be wounded in battle. But their wounds are not mortal and are easily healed.

One thing I try not to do when I read the Iliad is assume that I am experiencing the Olympians the way that Homer’s audiences experienced them. Was the piety of the Greeks of Homer’s time wholly perfunctory? The gods inspired awe and fear, but did a Greek ever love any of them? Was a Greek’s worship of a god ever a matter of disinterested adoration? Scholars may have answers to these questions. I have not found answers in my reading of the Iliad.

About Those Battles

Much of the Iliad is taken up with battles, usually between a single Greek and a single Trojan, although sometimes a god or goddess intervenes to aid one or the other of the warriors. These battles can at first produce an effect of monotony for some readers. But even here, Homer’s invention is unflagging. Alexander Pope observed in the preface to his translation that “No two heroes are wounded in the same manner, and [there is] such a profusion of noble ideas, that every battle rises above the last in greatness, horror, and confusion.”

Homer always gives us a short obituary of the warrior who is killed; in some cases this is only the name of his father and the place of his birth. In others, it may be an anecdote about the dying warrior’s youth and exploits. When I first read the Iliad, I found these short obituaries to be annoying and a distraction from the main business of the poem. Let’s get on with the story, my modern reading mind said.

But Homer’s readers, we can assume, were not as eager as we are in wanting to get on with the story. They knew the story already.

Homer not only depicts the horror of war. He also depicts the joy that warriors take in winning glory by killing other warriors. Of course, they hate the war, and when the Greek and Trojan leaders agree to settle the issue between them by single combat between Menelaus and Paris, warriors on both sides cheer the prospect of a quick end to the war. Still, it is the limitation of Simone Weil’s profound essay, “The Iliad, or the Poem of Force”, that she does not acknowledge the seductive power of war. Robert E. Lee is supposed to have said, “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it.” That remark is a better guide to the Iliad than Weil’s passionate detestation of force.

The Beauties of Nature in the Iliad

Homer is observant of nature, but in the Iliad descriptions of nature are almost entirely found in similes, which usually occur at climactic moments of battle. He almost never introduces description of nature for its own sake.

Similes serve to intensify emotion by drawing attention to something, such as the dying moments of a wounded warrior:

As within

A garden droops a poppy to the ground,

Bowed by its weight and by the rains of spring,

So drooped his head within the heavy casque.

Homer’s similes often compare things that strike modern readers as incongruous. This is because he is interested only in a particular quality shared by the things compared, as for example, the drooping of a poppy bowed down by its weight and the drooping of a warrior dying of wounds. Again, the falling of warriors in battle is like the falling of severed handfuls of wheat or barley as reapers advance across a field:

As when two lines of reapers, face to face,

In some rich landlord’s field of barley or wheat

Move on, and fast the severed handfuls fall,

So, springing on each other, they of Troy

And they of Argos smote each other down,

Homer’s most famous simile occurs at the end of Book Eight, which recounts a prolonged battle on the plains before the citadel of Troy. The Trojans, profiting from the absence of Achilles from the war and the neutrality of the gods, have advanced almost to the Greeks’ camp. They pitch camp when night falls:

So, high in hope, they sat the whole night through

In warlike lines, and many watch-fires blazed.

As when in heaven the stars look brightly forth

Round the clear-shining moon, while not a breeze

Stirs in the depths of air, and all the stars

Are seen, and gladness fills the shepherd’s heart,

So many fires in sight of Ilium blazed,

Lit by the sons of Troy, between the ships

And eddying Xanthus: on the plain there shone

A thousand; fifty warriors by each fire

Sat in its light. Their steeds beside the cars—

Champing their oats and their white barley—stood,

And waited for the golden morn to rise

The comparison of the Trojan campfires to the stars in the sky is not merely visual; it is also suggestive of the size of the Trojan army camped on the plain and ready for battle at first light. The calmness and beauty of the things compared — campfires and stars — makes an ironic contrast with the horror that is to be renewed in the morning:

The Trojans thus kept watch; while through the night

The power of Flight, companion of cold Fear,

Wrought on the Greeks, and all their bravest men

Were bowed beneath a sorrow hard to bear.

As when two winds upturn the fishy deep—

The north wind and the west, that suddenly

Blow from the Thracian coast; the black waves rise

At once, and fling the sea-weed to the shore—

Thus were the Achaians troubled in their hearts.

This is a more complex simile than most other of Homer’s. It first compares, implicitly, the Trojans who are pressing hard on the Greeks to the north and west winds pressing hard on the sea; and it compares the troubled state of the sea to the troubled state of the minds of the Greeks. The intensity of the storm at sea is suggested neatly by one detail, that it flings seaweed on the shore.

Homer’s similes give evidence of an observant love of nature on the part of the Greeks, but their purpose is not, as an end in itself, to describe nature. Their purpose is to illustrate and adorn the theme of the Iliad, the tragedy of warriors risking and meeting death in their quest for undying honor.

(I’m not sure what this means, but the classical writers, both Greek and Latin, use simile freely but metaphor almost never. “Oh my love is like a red, red rose” could be elaborated without offense to reason, and therefore would be acceptable to classical writers. But they would not tolerate “Oh my love is a red, red rose” , having no taste for surrealism.)

How I Read the Iliad

Modern readers of the Iliad form a different sort of audience from Homer’s original audiences, just by being readers rather than hearers. This means that we readers may be missing things that Homer’s original audiences may have picked up easily. The Homeric rhapsode may have varied his tone of voice in recitation to emphasize the emotions of the speakers or Homer’s ironies. Of course, we have never heard the Iliad recited as it was in the eighth century B.C. But it seems improbable that rhapsodes recited it with an inexpressive affect.

Here are a couple of ways I changed the way I read in order to read Homer better.

I Don’t Skim

One of the benefits of reading the Iliad is that it forces me to break the bad reading habits that I keep forming and reforming when I read contemporary throw-away stuff — detective novels and thrillers and other things that you would never think of reading carefully, or reading a second time.

The chief of these bad habits is skimming. When I recently read a detective novel, I got confused several times because I had skimmed over important details. But I didn’t flip back to find the details that I had missed because I knew that the details would be repeated a little farther on in the story. And they were repeated, because the author of the book expects his readers to skim and miss things.

You cannot read the Iliad this way. (Or Plato or Virgil or Dante or almost any other classical writer.). No classical writer expected to be read casually, nor would they ever have tried to accommodate casual readers.

The classics are really written. Everything counts, although parts of the poem do not all have the same degree of importance.

I Do Not Expect Homer to Explain Things To Me

It took me a while to get used to the fact that Homer expects the members of his audience to grasp the import of the things that are said and done in the Iliad. He lets things speak for themselves. Homer present you with only what you need to see or hear and nothing more.

Homer’s narrative style reminds me of the great passages of Old Testament narrative:

And David sat between the two gates: and the watchman went up to the roof over the gate unto the wall, and lifted up his eyes, and looked, and behold a man running alone.

And the watchman cried, and told the king. And the king said, If he be alone, there is tidings in his mouth. And he came apace, and drew near.

And the watchman saw another man running: and the watchman called unto the porter, and said, Behold another man running alone. And the king said, He also bringeth tidings.

And the watchman said, Me thinketh the running of the foremost is like the running of Ahimaaz the son of Zadok. And the king said, He is a good man, and cometh with good tidings.

And Ahimaaz called, and said unto the king, All is well. And he fell down to the earth upon his face before the king, and said, Blessed be the Lord thy God, which hath delivered up the men that lifted up their hand against my lord the king.

And the king said, Is the young man Absalom safe? And Ahimaaz answered, When Joab sent the king’s servant, and me thy servant, I saw a great tumult, but I knew not what it was. And the king said unto him, Turn aside, and stand here. And he turned aside, and stood still.

And, behold, Cushi came; and Cushi said, Tidings, my lord the king: for the Lord hath avenged thee this day of all them that rose up against thee. And the king said unto Cushi, Is the young man Absalom safe?

And Cushi answered, The enemies of my lord the king, and all that rise against thee to do thee hurt, be as that young man is.

And the king was much moved, and went up to the chamber over the gate, and wept: and as he went, thus he said, O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! would God I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son.

Here is a narrative style that limits itself rigorously to things seen and heard.

Homer’s style, apart from rare editorial comments, is similarly spare. We are not told what to think when shown that Hector’s shield covers him from neck to ankles:

So the plumed Hector spake, and then withdrew, While the black fell that edged his bossy shield Struck on his neck and ankles as he went.

Very rarely, however, Homer will comment on the action. The Greek Diomedes and the Trojan ally Glaucus meet in the midst of battle and quickly realize that their families have been friends in the past. Diomedes says:

And let us in the tumult of the fray

Avoid each other’s spears, for there will be

Of Trojans and of their renowned allies

Enough for me to slay whene’er a god

Shall bring them in my way. In turn for thee

Are many Greeks to smite whomever thou

Canst overcome. Let us exchange our arms,

That even these may see that thou and I

Regard each other as ancestral guests.”

Thus having said, and leaping from their cars,

They clasped each other’s hands and pledged their faith.

Then did the son of Saturn take away

The judging mind of Glaucus, when he gave

His arms of gold away for arms of brass

Worn by Tydides Diomed—the worth

Of fivescore oxen for the worth of nine.

Homer does not tell us, however, what Diomedes intended when he proposed this exchange, so profitable to himself.

Some Negative Counsels

The Iliad was composed a long time ago — so long ago that its age can be expressed in geological time; that is, it was composed a little more than 2,500 years ago, which is fully a fourth or third of the amount of time since the last ice age ended. A poem that old is bound to be informed by attitudes toward life and death that are very different from ours.

To understand and enjoy Homer, it is necessary to be aware of the difference between Homer’s assumptions about life and death and our own. Of course, if we could not agree with Homer about certain basic truths, he would be not merely foreign to us, but unintelligible. This is not the case.

I have formed some negative counsels for myself to steer me away from assumptions about Homer that I’ve come to think are false; as follows:

Do Not Look For Similarities Between Warriors and Us

Do not assume that the Iliad’s claim to “relevance” depends on the Homeric warriors being just like us, after all. It is true that if human nature had not been fundamentally the same in Homer’s time as it is today, the Iliad would be largely unintelligible to us. At the same time, the world of the Homeric warriors was bound by conventions and codes of behavior that are alien from ours. When Homeric warriors behave in ways that are repugnant to us, the reason is not that Homer has chosen to celebrate an unusually bad group of men. Homer’s warriors were honorable men seeking glorify, the most honorable of all pursuits according to the ethos of the warrior class.

Do not try to find an anti-war message in the Iliad.

Paradoxically, the work of literature that describes the savagery and terror of war better than any other has no anti-war message for us, because Homer accepted war as one of the permanent features of human existence. (This remark applies equally well to Jean Renoir’s masterpiece “La Grande Illusion”, which many reviewers refer to as an anti-war movie.)

Do Not Expect Homer’s Warriors to Think and Act Like Christians

Do not expect Homeric warriors to behave as if they had been present at the Sermon on the Mount. Turning the other cheek and forgiving one’s enemies may be, for us, the foundation of morality; for Hector or for Odysseus it all would have been nonsense.

Resist facile comparisons.

A recent translation of the Iliad was published with a photograph on the cover of allied troops landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day, June 6, 1944. The publisher’s intention was understandable: to interest people in buying and reading this book by suggesting that its content is of enduring relevance, even to this day. But the soldiers who fought on Omaha Beach were were not Homeric warriors fighting for personal glory; they were parts of a vast military machine dedicated to achieving certain ends of its own, employing thousands of nearly anonymous soldiers who wore “dog tags” to identify their corpses by number.

Resist the Lure of Extra-Literary Questions

Any approach that you make to the Iliad will reveal to you whole fields of questions that are fascinating in themselves but that have only a slight bearing on the appreciation of the Iliad as poetry. These questions concern the historical reality of wars waged by Greeks against Trojans; the evolution and nature of the Homeric dialect; the question of authorship; the accuracy of the Iliad’s portayal of the implements and tactics of warfare; and so on.

These questions, as I wrote, are fascinating, but the answers to them would be of little help to readers hoping to grasp the Iliad as imaginative literature.

For example, the American scholar Milman Parry (1902 – 1935) discovered that the Homeric dialect has features that were meant for the convenience of rhapsodes who composed and recited epic poems without the use of writing. Parry’s exposition of these features has the fascination of a great detective solving a puzzle that had defied attempts by generations of scholars to solve it. When Parry’s discoveries first became known, many scholars believed that they would greatly help the appreciation of Homer’s works as poetry, but this has not happened. Parry’s discoveries simply demonstrated the extreme likelihood of what scholars had long suspected, that Homer composed his epics without the use of writing.

Similarly, questions about the historical reality of the Trojan War are fascinating, but knowing that a Trojan War did or did not take place would do little to help us understand and enjoy the Iliad.

The recommended reading listed at the end of this post includes the names of several books about the Iliad’s historical background, dialect, and so on. This essay makes no further mention of these questions.

The Iliad and the Tragic View of Life

The Iliad does not palliate death in any way: it shows it to be the final and absolute destruction of the personhood of the warrior. William Collins’ (1721 – 1759) poem “How Sleep the Brave” is illuminating in this context because its treatment of death of is, in almost every possible way, unHomeric:

How sleep the brave, who sink to rest

By all their country's wishes best!

When Spring, with dewy fingers cold,

Returns to deck their hallow'd mold,

She there shall dress a sweeter sod

Than Fancy's feet have ever trod.

By fairy hands their knell is rung;

By forms unseen their dirge is sung;

There Honor comes, a pilgrim grey,

To bless the turf that wraps their clay;

And Freedom shall awhile repair

To dwell, a weeping hermit, there!

Spring does not return each year to decorate the Homeric warrior’s grave, the sod in which he is laid is not sweet, and his tomb is not blessed by personifications of Honor and Freedom. Homer knew nothing of such conceits, and would have found them to be the evasions of a mind too sickly weak to face the truth.

William Carlos Williams (1883 – 1963), in the second half of his poem “Death”, comes close to the Homeric view of death:

He’s nothing at all

he’s dead

shrunken up to the skin

Put his head on

one chair and his

feet on another and

he’ll lie there

like an acrobat—

Love’s beaten. He

beat it. That’s why

he’s insufferable—

He’s come out of the man

and he’s let

the man go—

the liar

because

he’s here needing a

shave and making love

an inside howl

of anguish and defeat—

which

love cannot touch—

just bury it

and hide its face

for shame.

Williams’ dead old man is not much like a dead Homeric warrior, but Williams like Homer sees that a dead man has “come out of the man” leaving nothing behind but an “it”.

Once dead, Homeric warriors are objects, mere ‘’prey for dogs and all birds’’. The gods may pity the Homeric warrior, especially if he has been a pious sacrificer at their altars, but there is little that even they can do for him when he dies.

Homer’s view of the relation of body and soul does not, like the Christian view, find the essence of human beings to be their souls, while their bodies are mere vessels of the soul that are cast off at the moment of death. Instead, Homer refers to the bodies of dead warriors as the warriors “themselves’’ (αὐτοὺς) — in contrast to their souls (ψυχὰς), which leave the bodies in the moment of death. The bodies become carrion, a ‘’prey for dogs and all birds’’, while the souls go to hell, where they are no more than smoke or shadows, without sense or volition. There is no recovery from this condition, no resurrection or redemption. Death, for Homer, is absolutely final.

It is a testimony to the tough mindedness of the ancient Greeks that a poem so desolate, so refusing of consolation, should have become a textbok for schools and the inspiration for later poets, historians, and tragedians.

The first work of literature produced in the western world — the Iliad — expresses a tragic view of life that is complete, entire, and deeply felt. There must have been earlier approaches to this tragic view, sketches or fumbled beginnings. They have been lost; not even references to them survive.

We as survivors of the twentieth century are well prepared to accept views of life that are tragic. What is harder for most of us to understand is the demand for glory that drove Homer’s warriors to kill and be killed. For between us and the world of those warriors lies the transforming emergence of Christianity, with its ethic of meekness and humility.

Choosing a Translation

The modern translations of the Iliad that I have read at least in part all seem to be accurate and scholarly — as far as I am qualified to judge. All these translations try to reproduce the original’s plainness and rapidity, and they do this fairly well.

The question “Which are the good translations?”, then, can only be answered personally. A good translation is one that you like well enough that it keeps you reading.

My two favorite translations are in verse, and by celebrated poets: Alexander Pope’s, published serially from 1715 to 1720, and William Cullen Bryant’s, published in 1871. I will say what I like about these translations below.

Differences Between Homeric Greek Versification and English Versification

Almost all modern translations are in verse. This surprises me, because poetry generally has lost its mass audience. I’m guessing that readers prefer verse translations of the Iliad in the belief that such translations must be truer to the style of the Iliad, which was itself in verse.

This belief is mistaken, for the most part. We can’t really know whether any verse translation reproduces the sound and feel of Homeric verse, because we don’t know what Homeric Greek sounded like when spoken by Homer’s contemporaries, and we have many questions about how Homeric verse produced the rhythms that distinguish it from prose.

We do know that Homeric verse differed from English verse in important ways.

All poetry in ancient Greek is quantitative; that is, it achieves rhythm through varying patterns of long and short syllables. The difference between long and short syllables in ancient Greek probably had something to do with duration, but we can only speculate.

The basic metrical unit of Homeric verse is the dactyl, a long syllable followed by two short syllables. A line of Homeric verse consists of five dactyls followed by a spondee (two long syllables). The final syllable in the line can be short instead of long.

Thus, a line of Homeric verse can be scanned like this:

LONG-short-short LONG-short-short LONG-short-short LONG-short-short LONG-short-short LONG-LONG (or LONG-short)

However, a spondee can be substituted for any of the dactyls. Spondees impart a slower, heavier movement to the line.

The possibility of substituting spondees for dactyls means that a line of Homeric verse can contain as many as 17 syllables (with no substitutions) and as few as 12 syllables (with spondees substituted for every dactyl). Such a variation in the number of syllables is not possible in the most common forms of English verse, which require a fixed number of syllable.

Traditional English poetry is accentual; that is, it achieves rhythm through patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables. The commonest metrical unit in English poetry is the iamb, consisting of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable; for example: be-GIN, re-VEAL. In place of any iamb, an English poet can substitute:

- A trochee, consisting of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one. For example: DIS-charge, RA-ven. Or,

- A spondee, consisting of two stressed syllables in succession. For example: DOWN-TOWN, DUMB-BELL, HUM-DRUM.

Although trochees and spondees can be used in place of iambs, most lines contain enough iambic feet to establish a predominant iambic rhythm.

The distribution of stresses on syllables in English can vary from speaker to speaker; I can hear some of my readers saying “Dumb-bell is a trochee! (You DUMB-bell.)” On some words, the stresses are on different syllables to indicate different meanings; for example, when friends present (preSENT) you with a birthday present (PREsent). The quantities of syllables of words in Homeric Greek are in most cases not variable.

A few older, classically educated English poets such as Spenser, Tennyson, and Bridges, have attempted to write quantitative verse in English, as experiments; it takes a finer ear than mine to detect rhythm in these experiments.

Longfellow used a dactylic hexameter line for his poem Evangeline, placing accented syllables where the Greek hexameter would place long syllables:

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks, Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight, Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic, Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms. Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.

We don’t know what Homeric verse sounded like, but it is not wild speculation to hold that it did not sound like Longfellow’s lovely verse.

One aspect of language, however, is more transferable from one language to another than most other aspects. This is syntax. Syntax has to do with the length and arrangement of clauses within sentences and of sentences within paragraphs. It can employ repetition and parallelism to achieve various sorts of emphasis. It can make poetry or prose stately and grave or brisk and lively.

The syntax of Homer’s verse is simple and unimpeded; it has an onward movement that carries your attention forward. Homer’s poetry was of unmatched greatness according to the testimony of the ancients, but it never tempts you to stop in your reading to savor particular felicities. It carries you along and forward. Any translation, in verse or prose, that reproduces Homer’s syntax is to that degree Homeric.

Below are my comments on the translation of Homer that I have read at least in part.

Chapman’s Homer

I love Keats’ sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer.” I wish I could love Chapman’s Homer, too, but I can’t. Its quirkiness calls attention to itself. I want translations that are self-effacing.

Here is how Chapman translated the beginning of the Iliad:

Achilles’ bane full wrath resound, O Goddesse, that imposd Infinite sorrowes on the Greekes, and many brave soules losd From breasts Heroique—sent them farre, to that invisible cave That no light comforts; and their lims to dogs and vultures gave. To all which Jove’s will gave effect; from whom first strife begunne Betwixt Atrides, king of men, and Thetis’ godlike Sonne. What God gave Eris their command, and op’t that fighting veine? Jove’s and Latona’s Sonne, who, fir’d against the king of men For contumelie showne his Priest, infectious sickness sent To plague the armie; and to death, by troopes, the souldiers went.

These lines have energy and bounce, but the oddness of Chapman’s diction wears me down after a few pages. And Chapman gets Homer wrong on an important point: Achilles’ wrath did not give the slain warriors’ limbs to dogs and scavenger birds — it gave them, the warriors, to dogs and scavenger birds. It is the Homeric identification of the warrior with his body that makes all the wounding and death in the Iliad so terrible.

Pope’s Iliad

Most readers’ feelings about Pope’s translation are bound up with their feelings about the Augustan rhymed couplet in general, of which Pope was the great master.

The literary scholar and teacher Patrick Cruttwell wrote:

I tried passages of Pope’s Iliad on my freshmen — and that did not work at all. They found it absurd, even indecent, to clothe material of such raw savagery in the formal diction and regular metre of Augustan verse. (These are the boys who can see Vietnam, night after night, on their TV screens; these are the boys who saw and heard the Inferno-like pandemonium after Robert Kennedy was shot.) Patrick Cruttwell, ‘’Six Phaedras in Search of One Phedre’’, in Delos: A Journal on and of Translation, 1968.

Professor Cruttwell’s students preferred Richmond Lattimore’s translation, about which see below.

De gustibus non disputandum est. I myself enjoy Pope’s Iliad as much as any other translation. It is lively and brisk; and, above all, it is poetry. Pope’s style is especially effective for rendering speeches such as Sarpedon’s address to Glaucus in Book 12:

Could all our care elude the gloomy grave

Which claims no less the fearful than the brave,

For lust of fame I should not vainly dare

In fighting fields, nor urge thy soul to war:

But since, alas! ignoble age must come,

Disease, and death’s inexorable doom;

The life which others pay, let us bestow,

And give to fame, what we to nature owe.

When I read passages such as this, I can hardly believe that anyone ever doubted that Alexander Pope is a poet. Matthew Arnold, in his essay “On Translation Homer”, wrote that Pope’s use of rhymed couplets for his translation imparts an unHomeric movement to it, and this is certainly true.

But Pope’s translation is the only English translation that is a work of genius, deserving to be counted among the masterpieces of English literature.

Bryant’s Homer

Another verse translation that I enjoy is by William Cullen Bryant, the poet, newspaper editor, abolitionist, defender of labor unions, and translator of the Iliad and the Odyssey. Bryant’s translation of the Iliad (1871) is in clear and elegant blank verse. As a poet, Bryant is best known for “Thanatopsis” and for “To a Waterfowl”, which Matthew Arnold wrote was the best short poem in the English language.pp

Here is Bryant’s translation of the first eleven lines of the Iliad:

O Goddess! sing the wrath of Peleus' son, Achilles; sing the deadly wrath that brought Woes numberless upon the Greeks, and swept To Hades many a valiant soul, and gave Their limbs a prey to dogs and birds of air, For so had Jove appointed, — from the time When the two chiefs, Atrides, king of men. And great Achilles oarted first as foes. Which of the gods put strife between the chiefs. That they should thus contend ? Latona's son And Jove’s. Incensed against the king, he bade A deadly pestilence appear among The army, and the men were perishing.

Lattimore’s Iliad

Richmond Lattimore (1986 – 1984) was a distinguished American classical scholar and translator. His translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey are prized for their line by line faithfulness to the original. Lattimore’s translations are so close to their originals that many people struggling through the original Greek use them as trots.

But it is just their closeness to the original that makes them, for me at least, almost unreadable.

Lattimore’s translations of Homer are printed with excellent scholarly introductions.

Recent Translations

In recent decades verse translations of the Iliad have been written by Robert Fitzgerald, Stephen Mitchell, Robert Fagles, Emily Wilson, and others. I myself do not see any reason to read these translations rather than the straightforward prose translations by Samuel Butler and E. V. Rieu, but a lot of people like them, and if they get people to read Homer, good for them.

However, Steven Shankman, editor of the valuable Penguin Classics edition of Pope’s Iliad, which he admires to the point of idolatry, has this to say: “It must be said, however, that in the achievement of perspicuity, modern poetic translators such as the accomplished and deft Robert Fitzgerald or the muscular Robert Fagles are often superior to Pope.”

But I would apply the “Hades” test to any modern translation before I commit myself to reading it. The beginning of the Iliad tells us that Achilles’ wrath sent warriors to Hades. Modern translators, wanting to spare their readers the humiliation of encountering names they don’t know, write phrases such as “the house of the dead” instead of Hades. This prevents the reader from understanding what Homeric warriors faced when they died, and why they found the prospect of feath terrifying. Hades was a god, the king of the dead, and a very unpleasant deity. His name was richly evocative of all that the Greeks found terrifying about the thought of death. There is no reason why modern readers should be prevented from ever encountering such references. Homer is weaker and paler when shorn of mythological references.

Do I Want to Study Homeric Greek?

The study of Homeric Greek rewards people who enjoy learning things. It frustrates people who want to know things, that is, who set knowing Homeric Greek as their goal. Greek in all of its dialects and historical varieties is a difficult language — complex, subtle, and full of inconsistencies. The things that make it difficult also help make it a language of unmatched expressive beauty and power, but it is not possible to separate what’s difficult from what is rewarding.

It is, however, fun to learn, and if you can tolerate being a novice for keeps, you might enjoy studying Homeric Greek. Henry David Thoreau was a student of Homeric Greek and read his Greek Iliad at Walden Pond almost daily. In the chapter in Walden titled “Reading”, he wrote:

It is worth the expense of youthful days and costly hours, if you learn only some words of an ancient language, which are raised out of the trivialness of the street, to be perpetual suggestions and provocations. It is not in vain that the farmer remembers and repeats the few Latin words which he has heard. Men sometimes speak as if the study of the classics would at length make way for more modern and practical studies; but the adventurous student will always study classics, in whatever language they may be written and however ancient they may be. For what are the classics but the noblest recorded thoughts of man? They are the only oracles which are not decayed, and there are such answers to the most modern inquiry in them as Delphi and Dodona never gave. We might as well omit to study Nature because she is old. To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. If you enjoy studying.

You are more likely to enjoy studying Homeric Greek if you have studied a highly inflected language such as Latin, German, or Russian. Having studied these languages will have made you familiar with important grammatical concepts in Homeric Greek, such as case, declension, agreement, voice, conjugation, and so on.

What the hell. Give it a try.

Some Books That Have Helped Me

On Translating Homer (1861), by Matthew Arnold.

Arnold identified the qualities of Homeric verse that a translator into English should aim to reproduce: rapidity, plainness and directness in thought and in the expression of it, and nobility. This essay has been extremely influential, and I’m sure that modern translators sense Arnold looking over their shoulders as the write.

The Iliad, or the Poem of Force (1939), by Simone Weil. This famous essay, published on the eve of World War II, is a profound meditation on the nature of violence. It is less valuable as a guide to the Iliad, because it fails to take into account the attraction of violence for the Homeric warrior. Robert E. Lee understood this attraction better; he said “It is well that war is so terrible; otherwise we might like it too much.”

On the Iliad (1943), by Rachel Bespaloff. This brilliant essay was published four years after Simone Weil’s essay, and some think as a response to it. Weil had written that force is “that x that turns persons into things.” Bespaloff agrees with Weil in detesting force, but also sees that force can, paradoxically, be an expression of life’s vitality.

Bespaloff writes perceptively about the chief characters in the story — Hector and Andromache, Achilles and Thetis, Paris and Helen, among others — and highlights the great artistry with which he wove them into the most tragic of stories.

Note: The essays by Weil and Bespaloff, in distinguished translations by Mary McCarthy, have been published together as a single title, War and the Iliad, by New York Review Books.

Homer (1980), by Jasper Griffin. This short essay by a great modern scholar is readable and filled with insight.

The Poetry of Homer (1938), by Samuel Eliot Bassett. The author, a professor of Greek at the University of Vermont, discusses the works of Homer as literature, the way scholars discuss the works of Shakespeare or Milton. He believed that scholars’ absorption by the fascinating questions of the origins and methods of composition of the Homeric poems had led to a neglect of Homer as poetry.

History and the Homeric Iliad, by Denys Page. This well-written book considers the evidence for an historical basis of the Trojan War.

Homer, by C. M. Bowra. This readable survey covers the historical and cultural background of the Homeric epics, as well as questions of their appreciation as literature.

The Justice of Zeus, by Hugh Lloyd Jones. This book argues that Zeus stood for discernible moral principles.

Appendix: How to Cuss Your Boss in Homeric Greek

The mainspring of the Iliad is the passionate quarrel that broke out between Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek forces at Troy, and Achilles, the greatest warrior among both the Greeks and the Trojans. In the course of the quarrel, Achilles addresses Agamemnon with these words, translated loosely:

Oh you who have grown fat from drinking wine — you who have the eyes of a dog and the heart of a deer!

In Homer’s Greek, hthese three curses occupy one full line:

οινοβαρες, κυνος ομματ´εχων, κραδιην δ´ελαφοιο

This line can be rendered phonetically as follows:

OY no bar ACE! coo nos OH mat ache AWN! craddy AIN della PHOY oh!

When you speak this line, drawl the capitalized syllables and speak the lower-case syllables quickly and crisply. And tell your boss that it means “Oh you who have the form and wisdom of a god/goddess!”

I’ve not studied Homeric Greek, but I’ve read the Iliad many times (the first time in high school) in several different translations (Fitzgerald, Lattimore, Pope, Bryant, and Fagles — my favorite is Bryant’s). Thanks very much for providing so much more about the Iliad than I ever knew — I can’t wait to read it again!

LikeLike

This is a very gratifying comment — that what I wrote makes you want to read the Iliad again.

LikeLike

I think their demand for glory that drove Homer’s warriors to kill and be killed is driven by their need to be remembered and recounted by their deeds…good and bad. Seeing how quickly the body decays and/or is consumed by animals on the battlefield probably helped enforce such an absolute view of death. It’s also extremely practical. Even burying a body involves a large amount of effort…whereas a funeral pyre is much more effective and scales.

Thanks for your post.

LikeLike

Yes, I think that glory was really the only kind of immortality that the warriors felt they could achieve. And the Greeks thought that the Iliad was an actual record of real heroes — proof the this kind of immortality could be achieved.

LikeLike

Bryant was a first rate poet, at least in one poem, “To A Waterfowl”:

Whither, ‘midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day,

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue

Thy solitary way?

Vainly the fowler’s eye

Might mark thy distant flight, to do thee wrong,

As, darkly seen against the crimson sky,

Thy figure floats along.

Seek’st thou the plashy brink

Of weedy lake, or marge of river wide,

Or where the rocking billows rise and sink

On the chaféd ocean side?

There is a Power, whose care

Teaches thy way along that pathless coast,—

The desert and illimitable air

Lone wandering, but not lost.

All day thy wings have fanned,

At that far height, the cold thin atmosphere;

Yet stoop not, weary, to the welcome land,

Though the dark night is near.

And soon that toil shall end,

Soon shalt thou find a summer home, and rest,

And scream among thy fellows; reeds shall bend,

Soon, o’er thy sheltered nest.

Thou’rt gone, the abyss of heaven

Hath swallowed up thy form, yet, on my heart

Deeply hath sunk the lesson thou hast given,

And shall not soon depart.

He, who, from zone to zone,

Guides through the boundless sky thy certain flight,

In the long way that I must trace alone,

Will lead my steps aright.

LikeLike

Terrific essay, John. Unlike you, I have only sampled more recent translations. We used to teach Robert Fitzgerald’s

LikeLike

Lance, Glad you liked it. The Fitzgerald essay is good — I didn’t mean to say it isn’t. When and where did you teach the Iliad?

LikeLike

I’ve been reading the Iliad again and seeing things I never saw before. I am convinced now that as a literary artist, Homer can hold his own against Joyce, Flaubert, James — at least!

We have to rid ourselves of the assumption (unacknowledged) that because we have flown in airplanes and been treated with antibiotics, we must be smarter than the ancients.

LikeLike