Lately I’ve been reading books by and about the classic American writers who lived in Concord, Massachusetts in the years before the Civil War — Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Fuller. My reading has given me definite ideas about what must have been the personal qualities of each of them. I would be surprised if, on meeting Emerson, I found him to be anything but smiling and serene, or Thoreau anything but serious and difficult to engage in conversation, or Hawthorne anything but shy, courteous, and brooding on evil, or Fuller anything but an epitome of critical intelligence. My ideas may be no more than caricatures, but they do have roots in what I have read.

But I had been unable to form any such definite idea about Bronson Alcott, who was a figure of consequence in that extraordinary community of writers and thinkers. Although he wrote almost daily, in a journal that grew to thousands of pages in the course of his long life, he never fully succeeded in revealing himself in his writing. That is, as far as I know; I haven’t read the volume of selections from his journals edited by his biographer Odell Shepard.

And yet, I am certain that he was an extraordinary person of some sort. He was taken quite seriously by distinguished writers whom we must take seriously. He became a close friend of both Emerson and Thoreau. At one time, Emerson and Alcott tinkered with the idea of combining their households to form a sort of transcendental commune. (Mrs. Emerson and Mrs. Alcott said no.). He lent Thoreau the ax that he used when building his hut at Walden Pond and he became a frequent visitor at the hut. He was entrusted with planning Thoreau’s funeral and memorial service. When a young poet named William Dean Howells paid Hawthorne a visit in Concord, Hawthorne told him that there were two more people whom he must see before he left town: Emerson and Alcott.

His acceptance by the great figures of Concord — he was a outsider from Connecticut — is all the more remarkable in that it occurred when Concord was beginning to attract cranks and and cultural sight-seers of all types, and the great figures in town were no doubt on guard against them. Alcott got through their defenses.

But for all that, I was able to picture him only as a failure — as a teacher, a writer, a thinker, and a breadwinner for his wife and four daughters. I’m missing something.

To begin my quest for Bronson Alcott, I looked up the main facts of his life in standard reference works, and found the following.

Amos Bronson Alcott (1799 – 1888) was born in Spindle Hill, Connecticut. His father was an unprosperous farmer and mechanic. Like Lincoln, Alcott had little formal education but made up for this lack by reading classics of English literature. Unlike Lincoln, Bronson did not become a distinguished writer. His very real gifts would lie elsewhere.

Growing up, he worked in a New England clock factory, and as a pedlar selling books in Virginia and the old Carolinas.

In 1830, Alcott married Abby May, the daughter of a prominent abolitionist. Through her personal connections, he became acquainted with William Lloyd Garrison and contributed an article to Garrison’s anti-slavery paper The Liberator. Alcott and his wife visited Garrison in jail on the day after Garrison had been rescued by authorities from a Boston lynch mob — jail being the best way that the authorities knew to protect him.

Visiting Garrison while the lynch mob was still no doubt violently agitated was a courageous and principled act, and not the first such act that Alcott would take. He later refused to pay taxes as a protest against the Mexican War — and was bailed out by friends. Thoreau admired Alcott’s courage and emulated him, even to the point of being bailed out by friends.,

But Alcott’s real vocation was not political agitation, but teaching.

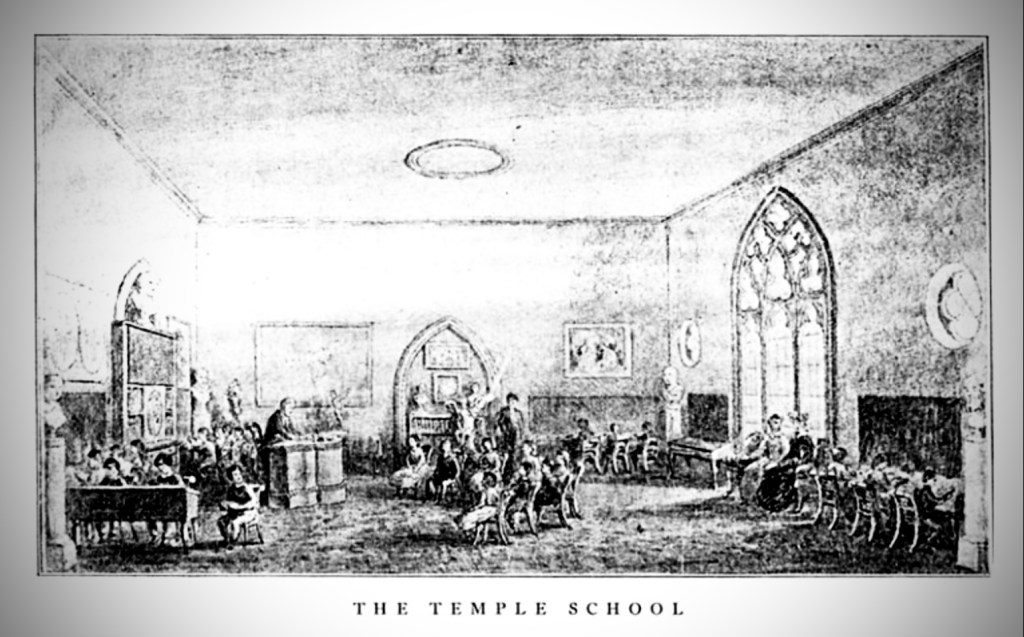

After teaching in several schools in New England and Philadelphia, he founded the Temple School in Boston. Here, in his own school, he had the freedom to follow his own unorthodox teaching philosophy, which stressed the development of the child’s personality rather than the inculcation of knowledge. This philosophy was based on his belief that children have within them illimitable funds of knowledge and wisdom. The teacher’s job, accordingly, is to elicit this knowledge and wisdom, to make it effective and working in the lives of pupils. And the way to draw out a pupil’s inner riches, Alcott believed, was through conversation. Alcott listened to his pupils as much as he spoke to them; he tried to engage them in dialectic of the kind practiced by his hero Socrates.

Even in the matter of discipline, Alcott refused to rely on his authority as the teacher, and instead adopted a collaborative and Socratic approach. When a pupil misbehaved, Alcott asked the other pupils to decide on a punishment. This would, Alcott believed, arouse in the pupils a sense of shame at their own misbehavior. It worked, according to later accounts of some pupils, but it disturbed some of the parents. The hickory stick reigned in American classrooms at this time. Thoreau lost his teaching job in the Concord public schools by refusing to cane his students.

Alcott’s classroom was decorated to reassure and inspire his pupils. The walls were covered with maps and with prints of such paintings as Guido Reni’s “Flight into Egypt”. Busts of Plato and Socrates and Milton were mounted on the walls, to remind students of the greatness of which the human spirit is possible. Dr. Johnson’s English Dictionary sat on Alcott’s desk, where it was displayed as a sacred ark of human knowledge.

Alcott was assisted in running his school by two brilliant women, Elizabeth Peabody and later Margaret Fuller. Peabody — whose sister Sophia married Nathaniel Hawthorne — would later open the first English language kindergarten in the United States and become a leading expert on early childhood education. Fuller would become a major figure of the transcendentalist movement. That Alcott was able to enlist the help of two such women is another indication that he was something more than a crank.

I have read different explanations of how Alcott’s school failed. One explanation is that it simply came to lack pupils. Some parents withdrew their children when they saw how unorthodox Alcott’s teaching philosophy was. The economic panic of 1837 forced other parents to withdraw their children.

According to another account, suspicions of heretical teaching led authorities to shut the school down. Alcott had been engaging his pupils in conversations about the meaning of the gospels. Elizabeth Peabody wrote a book about the conversations. A Boston attorney bought 750 copies of the book in order to destroy them. When a sheriff appeared at the door of the school holding a copy of the decree that the school must be closed, Alcott’s little daughter Louisa May confronted the sheriff and said, “Go away, bad man, you are making my father unhappy!”

Later, Alcott would open a small version of the Temple school, and would again outrage public opinion, this time by accepting a black girl as one of his pupils.

After the Temple school failed, whatever the reason, Alcott moved his family to several different towns before settling in Concord in 1840, some say at the urging of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The family lived in poverty alleviated occasionally by earnings from Alcott’s lecturing. Lecturing could be a lucrative occupation in that era, as Emerson and Mark Twain were showing, but Alcott’s style of lecturing would never become popular. He called his lectures “Conversations” and expected members of his audience to do at least half of the talking. The truth will emerge through dialectic, he told his bewildered ticket holders. In the end, though, few people cared to spend money on tickets only to hear themselves talk,

He founded a short-lived community to be based on principles of virtue and the sharing of wealth. The members of the community were to sustain themselves by farming, and their enterprise, accordingly, was named Fruitlands. This project, perhaps the noblest of all projects undertaken by Alcott, contributed by its failure to Alcott’s reputation as an impractical visionary.

Increasingly, the Alcott family was supported by Louisa May, whose books Little Women, Little Men, and Jo’s Boys became (and remain) best sellers. Bronson’s diaries record the great pride that he took in his daughter’s success.

In 1859 he was appointed superintendent of the Concord School System, a job he held until 1865. I have been unable to find out who was behind the appointment; whoever it was, the appointment indicates that Alcott was held in esteem by Concord’s civic leaders.

As superintendent, Alcott found, rather late in life, a paying job for which he was well suited. He visited classrooms throughout the district, encouraging a more spontaneous and joyous style of teaching and learning than was then customary. He invited Thoreau to visit classrooms and talk to students about nature, and to write a natural history of Concord for use in the schools. Thoreau liked these ideas but was too sick with tuberculosis to act on them.

In 1879, Alcott and the former abolitionist Franklin Sanborn founded the Concord School of Philosophy, which Alcott hoped would become a modern Plato’s Academy. The school was housed in a building constructed on the grounds of the Alcott House. It hosted lecturers who spoke about modern philosophers such as Kant and Hegel, as well as transcendentalists and the abolition movement. The school closed in 1888 with a memorial lecture about Alcott, who had recently died.

In his old age, Alcott lived quietly, receiving visits from guests and admirers who regarded him as a sort of oracle. Of course, others regarded him as a crank, and in fact the jury remains out on the value of his claim on our attention. But that is just question that I set out to answer for myself.

That is what the reference works tell me. It’s a picture frame waiting for a portrait. Fortunately, his gifted acquaintances were good portrait painters.

Of all his gifted friends, Alcott was probably closest to Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson met Alcott in Boston in 1835 and the two got along well from the beginning of their acquaintance.

Scholars and readers have speculated about why Emerson took to Alcott so quickly. My guess is that in Alcott, Emerson saw a reflection of his own unfallen nature.

Henry James Sr., who knew Emerson well, wrote that Emerson lacked a conscience, by which he meant that Emerson had no sense of ever having sinned. Emerson never tasted of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. He didn’t reflect on his own good intentions; he simply took the goodness of his intentions for granted.

And in fact, Emerson was instinctively virtuous, so much so that James was outraged when he saw Emerson enjoying a cigar and a drink at a literary banquet in Boston. It was the desecration of an otherwise immaculate temple, James felt.

Alcott, similarly, was virtuous by instinct, without his left hand knowing what his right hand did. Alcott would be the subject of many entries in Emerson’s journals, and it is from these that I draw most of my idea of Alcott as a person.

In his journal entry for October 21, 1835, Emerson wrote: “Last Saturday night came hither Alcott & spent the Sabbath with me. A wise man, simple, superior to display & drops the best things as quietly as the least.” Much later Emerson is known to have described Alcott as “a tedious archangel”, but he never seems to have lessened his regard for Alcott’s character. Emerson’s biographer Robert Richardson believed that Emerson may have had Alcott in mind when he wrote his essays on “The American Scholar”:and “Character”. The latter essay begins:

“I have read that those who listened to Lord Chatham felt that there was something finer in the man, than anything which he said. . . . This inequality of the reputation to the works or the anecdotes, is not accounted for by saying that the reverberation is longer than the thunder-clap; but somewhat resided in these men which begot an expectation that outran all their performance. The largest part of their power was latent. This is that which we call Character, — a reserved force which acts directly by presence, and without means.”

In a journal entry dated March — April 1842, Emerson wrote:

He [Alcott] delights in speculation, in nothing so much and is very well endowed & weaponed for that work with a copious accurate, & elegant vocabulary; I may say, poetic; so that I know no man who speaks such good English as he, and is so inventive withal. . . . Where he is greeted by loving and intelligent persons his discourse soars to a wonderful height, so regular, so lucid, so playful, so new & disdainful of boundaries & experience, the the hearers no longer seem to have bodies or material gravity, but almost they can leap into the air at pleasure, or leap at one bound out of this poor solar system

Emerson the notes with regret that Alcott could not transfer his wonderful flow of words and speculation to paper. In the following excerpt from an essay by Alcott, something is struggling for articulation and form but does not succeed:

Nature is quick with spirit. In eternal systole and diastole, the living tides course gladly along, incarnating organ and vessel in their mystic flow. Let her pulsations for a moment pause on their errands, and creation’s self ebbs instantly into chaos and invisibility again. The visible world is the extremist wave of that spiritual flood, whose flux is life, whose reflux death, efflux thought, and conflux light. Organization is the confine of incarnation,—body the atomy of God.

Reading this, I am reminded of Tertan, the brilliant and altruistic university student of disordered mind who is the central figure of Lionel Trilling’s short story “Of This Time, of That Place”. Tertan’s literature professor encourages Tertan to express his ideas intelligibly, without success. I was tempted, when first thinking about Alcott, to find evidence of mental illness in his words and actions, but the more I read and thought about him, the less this seemed to account for him. Alcott was certainly sane. And like Tertan, he had a gift for disinterested love. Although he must have been frustrated by his own failure as a writer, he took pride in the success as writers that his daughter Louisa May and his friend Henry David Thoreau were enjoying. He seldom quarreled with anyone, and remained on good terms with people who told him that he was ludicrous or dangerous.

Emerson further noted that Alcott never lost his belief in a benevolent superintending Deity, and this at a time when Darwin’s discoveries and the Higher Criticism of biblical texts were undermining the faith of Christians, Alcott remained convinced of the truth of most Christian teachings. His simple unquestioning belief in life after death led to his often being asked to console children who had lost family members.

Being human, Bronson Alcott must have done his share of mean and shabby things, but none are recorded — and it’s hard to imagine him doing them. His inability to make money created much hardship for his wife and family. Louisa May resolved not to become financially dependent on a man, and never married. But of intentional cruelty toward those he loved, I’ve read nothing.

Alcott may best be understood, then, as an unfallen spirit in a fallen world. That much we can say, but it doesn’t come close to making up for what we will forever lack, the experience of listening to him talk so brilliantly and unselfconsciously, out of the fullness of a mind that retained, through a long life of failure and turmoil, its stubborn, undefeated innocence.

NOTE. The books that are most helping me in my quest for Alcott are:

— Pedlar’s Progress: the Life of Bronson Alcott, by Odell Shepard

— Books about Emerson, Thoreau, or the Transcendentalists by Robert Richardson

— The essays of Emerson

— Selection from Emerson’s Journals, edited by Joel Porte.

Good luck with your search — Alcott seems to have been one of those people whose conversation was brilliant and left mainly to the imagination of successive generations. He had the bad luck to have flourished in the epoch before audio recording. I’ve heard that Clarence King, member of the Five of Hearts and friend of among others Henry James and Mark Twain, was another. How much other such brilliance has been lost to us?

LikeLike

C.M Bowra, the Oxford classicist, was the most brilliant conversationalist at Oxford in his generation, but his prose was undistinguished. Go figure. On the other hand, Oliver Goldsmith was a brilliant writer but made a fool of himself whenever he tried to shine in conversation.

LikeLike