Huckleberry Finn — that is, both the boy as he exists in popular imagination and the book by Mark Twain — has taken up a lot of space in the minds of Americans since the book was published in 1884. Or possibly the boy may have been taking up too much space and the book not enough. When Ronald Reagan wanted to stress the idyllic nature of his childhood in Illinois, he said that he had had a “Huck Finn sort of boyhood”. Really? Had he narrowly escaped being murdered by his drunken, ax-wielding father? Clearly, the boy needs to be corrected by the book. And perhaps the book itself needs to be corrected — or brought into better focus — by comparison with another book, such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

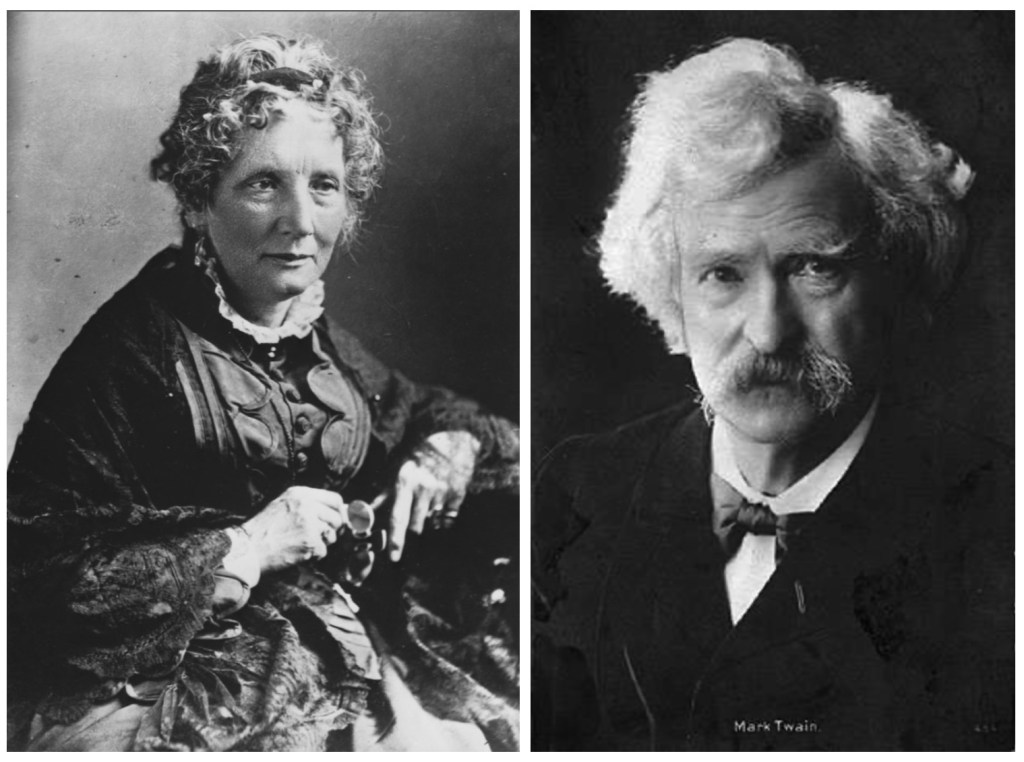

My wife and I recently read Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin — that is, I read it out loud while she followed along in her own copy. We didn’t know quite what to expect when we started to read it. We knew that it is often described as a work of propaganda — propaganda for a righteous cause, to be sure, but still propaganda. We knew that as propaganda, it had been effective like no other book before it in American history had been, not even Thomas Paine’s appeals to the revolutionary spirit of the American colonials. Whether or not Lincoln said that Stowe and her book were the cause of the Civil War, there is no doubt that it hastened the coming of the war by making the depth of the country’s division of conviction and feeling about slavery impossible to ignore.

As we read Uncle Tom’s Cabin, we were surprised to find that it is powerful not only as a political tract, but also as a work of fiction. The characters in the book are believable and vividly drawn, and the story is deeply moving. The main character in the story, Uncle Tom, is dignified and courageous; the events leading to his death are harrowing; and his death is the most terrible to read in all the literature that I know.

We had also recently read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, in a book discussion group, and that book was still fresh in our minds. It was natural to compare Huckleberry Finn with Uncle Tom’s Cabin; both books deal with racism, and both had become controversial on that account. Both were written at roughly the same distance in time from the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865, which abolished slavery: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852, came 13 years before, and Huckleberry Finn, published in 1884, came 19 years after. The comparison gave us a better sense of both books.

My wife prefers Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and I prefer Huckleberry Finn, although we each like both books. My wife admires Stowe’s strong clear prose and her unforced moral outrage. I admire, to the point of idolatry, the music of Huck’s easy flow of dialect, and his humor, and his ironies (conscious and unconscious).

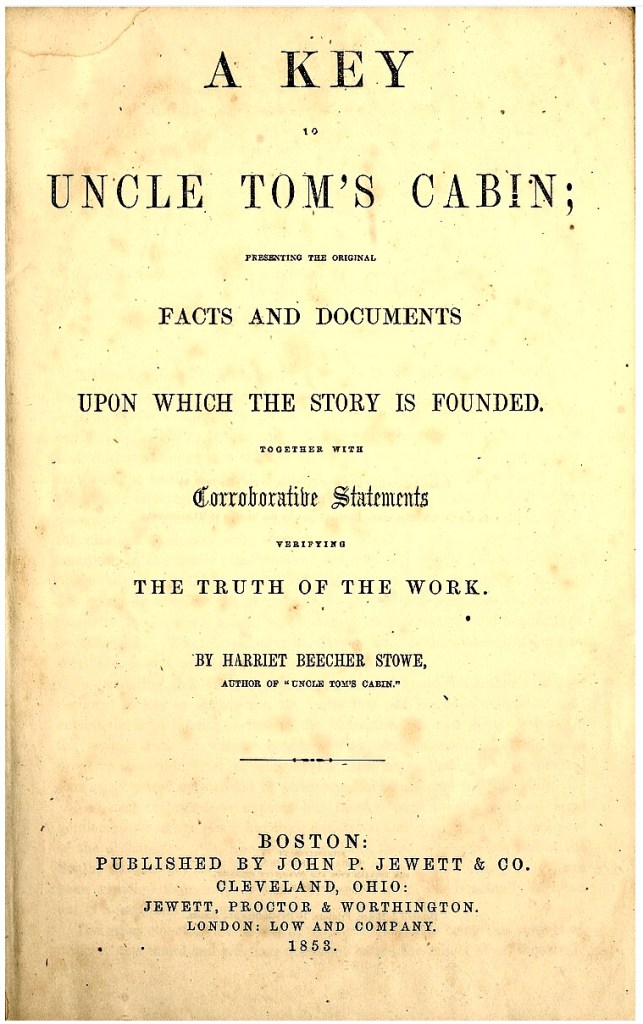

We knew that both books had from the beginning been reviled by large numbers of Americans; and that both books had been banned in many places. Harriet Beecher Stowe was accused by defenders of slavery of having made up most of the incidents on which the book’s condemnation of slavery is based. Mark Twain was accused of having promoted racism by including racial slurs in his book’s dialog — critics have even counted the number of times (213) that the N-word appears in the book.

But both Stowe and Twain worked hard to get the factual basis of their books right. Stowe based every important incident in her book on a verified event, and she documented her sources in a book titled A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Presenting the Original Facts and Documents.

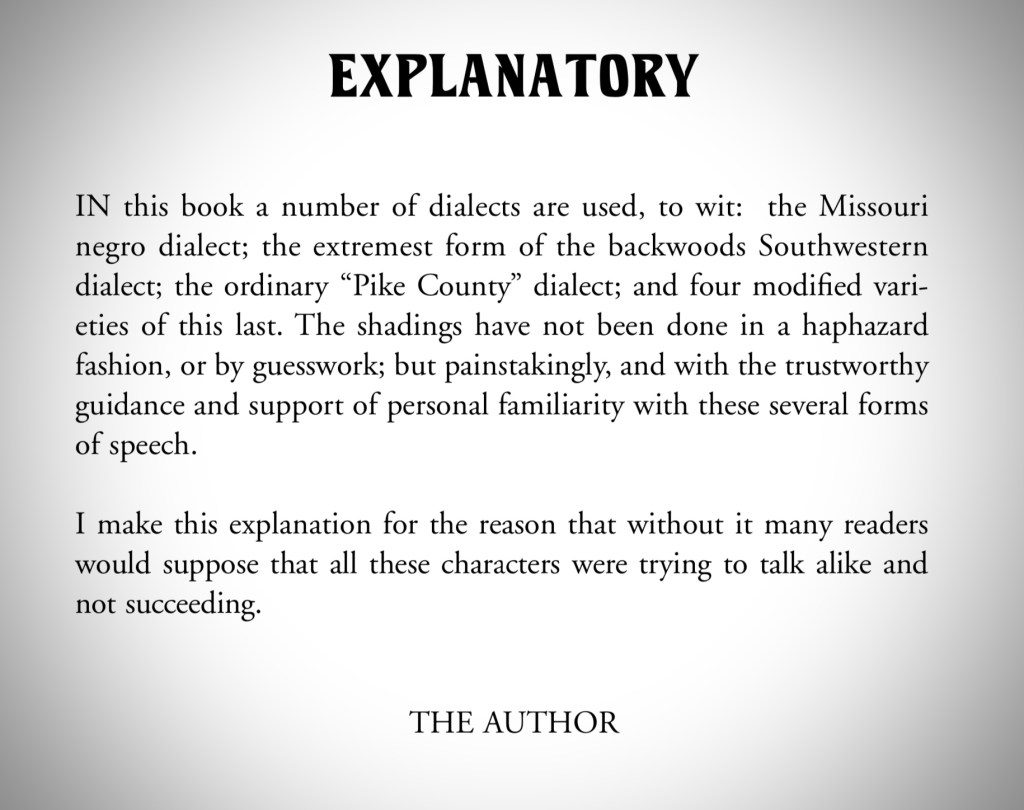

Mark Twain put the following note at the beginning of Huckleberry Finn:

This note should make it clear even to the most captious critic that Twain included racial slurs in his book only because such language was in fact spoken by the people on whom he based the characters in his book. The N-word was part of their dialects. Of course, it was as hateful a word then as now. But Twain’s love for the world of his youth would not allow him to idealize it.

We felt quite superior to the critics of our two books — but more so to the critics of Huckleberry Finn, who seemed to us to be especially literal minded and obtuse.

But then I ran across an article about Huckleberry Finn by a distinguished novelist and critic who shares our admiration for Uncle Tom’s Cabin but has strong dislike, verging on contempt, for Huckleberry Finn. I will not mention the name of this novelist and critic (“N&C” going forward), who will likely have admirers among you who are reading this. N&C is, at any rate, someone whose thoughts I have to take seriously.

N&C’s general criticism of Huckleberry Finn is that Twain’s treatment of Jim’s quest to gain his freedom lacks the seriousness that so great a subject deserves. Although Jim’s humanity is magnificently affirmed when Huck apologizes to him for having played a cruel practical joke on him, Jim is otherwise a diversion, a figure of fun, rather than anything like what he would have been in fact — the central figure in the tragedy of a family destroyed, its members separated from each other, all of its hope stifled.

Twain’s portrayal of Jim at times amounts to caricature, N&C objects. He is shown to be ignorant, superstitious, and weak. He lacks Uncle Tom’s dignity and strength. Among whites he assimilates himself to what whites want him to be — mere chattell, that is, “a personal possession other than real estate.” It is only on the raft, in the middle of the river, far from whites (except Huck), that Jim ever lays claim to the dignity and freedom that are properly his as a man.

(It seems obvious to me that we modern readers are not in a position to judge whether Twain’s depiction of Jim is accurate as to his speech, his beliefs, or his character generally. We do know that Twain worked hard to reproduce as accurately as possible the different dialects spoken by his characters, so that Jim’s manner of speaking is probably drawn from life. And we can assume that if Twain had produced, in Jim, a mere racist caricature, there would have been people alive when the book was published who could have called this out from first hand knowledge.)

Another sign of Twain’s lack of seriousness about Jim, says C&N, is the plan that Jim and Huck form of going down the Mississippi only as far as the mouth of the Ohio, where they would find a steamboat on which to travel up the Ohio as far north as they could go. Implausible! says C&N. From Jackson Island, Jim and Huck could have looked to the east and seen the free soil state of Illinois. Once there, Jim would have been free. Twain didn’t make them cross over to Illinois because he wanted them try for the mouth of the Ohio, and miss it, and so be carried helplessly down stream toward all the adventures that he had in mind for them.

But Jim and Huck’s plan might have seemed reasonable to Mark Twain. Although Illinois was a free state, the white population of southern Illinois was violently racist; in 1837, roughly the time of Huck Finn’s adventures, a pro-slavery mob murdered the abolitionist printer Elijah Lovejoy in Alton, Illinois. Mark Twain would have felt, then, that it would be implausible for Jim and Huck simply to cross the river into Illinois. Welcome to the dark wood of speculation!

For most of the rest of the book, the question of Jim’s fate is set aside to make way for numerous digressions — the con men who come on board the raft, the feud between the Grangerfords and Shepherdsons, Colonel Sherburn and Boggs, and so on. Most annoying and offensive of all is the appearance of Tom Sawyer at the end of the book; from this point on, Jim’s fate is no longer set aside, but is made the substance of an elaborate charade in which Tom makes Jim play the part of a prisoner in one of the adventure stories that Tom so loves.

Jim has, of course, been freed by the terms of the will of his owner, who has died. Tom knows this, but keeps this joyous news to himself, making him all the more a jerk.

No, says C&N, it’s wrong to mix the profoundly serious matter of a man’s struggle for freedom with the stuff of a boy’s adventure story. In Tom Sawyer, Twain kept serious matter in the background, mostly, and produced a nearly perfect prose poem about the world of his boyhood. In Huckleberry Finn, Twain’s attempt to mix adult seriousness with boyish fun produced an artistic and moral disaster.

These are serious criticisms and Huckleberry Finn would stand justly condemned by them, if they weren’t based on a wrong idea about what Huckleberry Finn is all about, and about what Mark Twain was attempting to do in writing it. The answer to these questions is found in the title of the book: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The book is not about Jim, or even, as some suppose, the Mississippi River. It is about Huck Finn.

The title might have been reworded, The Moral Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, for the book is about Huck’s growth in moral understanding in the course of his trip down the Mississippi River in the company of a runaway slave. Such a story would inevitably raise issues of justice and race, but Huckleberry Finn could not be the same sort of book as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Mark Twain was writing in and for a different world from the world in which Uncle Tom’s Cabin was written. Stowe could appeal to the anti-slavery fervor that was overtaking the North. Twain had to appeal to a public that had turned away from moral crusades. In particular, the white book-buying public had lost interest in the fate of the former slaves. It had cost four years of hellish blood letting to free them — wasn’t that enough? If Mark Twain was interested in raising the issues of race and justice that he well knew needed to be raised, they would have to be raised indirectly; for example, in an account of a young boy’s moral education.

But it could not be an ordinary boy. Perceptive readers of Huckleberry Finn could not have been long in noticing that the central figure of this new book possessed empathy for others in an extraordinary degree. He is often “in a sweat” for people in danger or trouble. Huck describes what he saw when he and Tom went out in the middle of the night to organize a band of robbers who would wreak havoc on their town, robbing the wealthy and taking hostages and ransoming the hostages — whatever that means.

Well, when Tom and me got to the edge of the hilltop we looked away down into the village and could see three or four lights twinkling, where there was sick folks, maybe; and the stars over us was sparkling ever so fine; and down by the village was the river, a whole mile broad, and awful still and grand. (emphasis added)

While Tom’s mind is filled with the imaginary glory that he and his band of robbers will achieve by inflicting misery on imaginary victims, Huck’s mind is filled with the real beauty of the river at night, and with the possibility that there are sick people in the rooms where lights are on.

Huck’s empathy extends to people who would not seem to deserve it. When Jim and Huck stop to explore a wrecked steamboat, they find a villainous gang of murderers on board, preparing to kill a man they accuse of cheating them. The steamboat starts to break up, and Jim and Huck abandon ship as quickly as possible. They take the murders’ row boat, for their raft had come loose and started to drift away:

Then Jim manned the oars, and we took out after our raft. Now was the first time that I begun to worry about the men—I reckon I hadn’t had time to before. I begun to think how dreadful it was, even for murderers, to be in such a fix. I says to myself, there ain’t no telling but I might come to be a murderer myself yet, and then how would I like it?

So says I to Jim:“The first light we see we’ll land a hundred yards below it or above it, in a place where it’s a good hiding-place for you and the skiff, and then I’ll go and fix up some kind of a yarn, and get somebody to go for that gang and get them out of their scrape, so they can be hung when their time comes.

Later, when Huck goes ashore to buy some supplies and is called up short by a terrible sight:

. . . and as they went by I see they had the king and the duke astraddle of a rail—that is, I knowed it was the king and the duke, though they was all over tar and feathers, and didn’t look like nothing in the world that was human—just looked like a couple of monstrous big soldier-plumes. Well, it made me sick to see it; and I was sorry for them poor pitiful rascals, it seemed like I couldn’t ever feel any hardness against them any more in the world. It was a dreadful thing to see. Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.

Another extraordinary quality of Huck Finn is his self-reliance. He is not eager to be a rebel. He hates to go against what he has been taught. But if what he has been taught is contradicted by what he feels and knows in his heart to be right, he follows his heart. In one of the most celebrated passages in the book, Jim upbraids Huck for having led him to believe that he had drowned:

When I got all wore out wid work, en wid de callin’ for you, en went to sleep, my heart wuz mos’ broke bekase you wuz los’, en I didn’ k’yer no’ mo’ what become er me en de raf’. En when I wake up en fine you back agin, all safe en soun’, de tears come, en I could a got down on my knees en kiss yo’ foot, I’s so thankful. En all you wuz thinkin’ ’bout wuz how you could make a fool uv ole Jim wid a lie. Dat truck dah is trash; en trash is what people is dat puts dirt on de head er dey fren’s en makes ’em ashamed.”

It is after this chastisement that Huck makes his famous decision to humble himself and apologize to Jim — a black man! — saying afterward that it felt right to have done so:

It was fifteen minutes before I could work myself up to go and humble myself to a nigger; but I done it, and I warn’t ever sorry for it afterwards, neither. I didn’t do him no more mean tricks, and I wouldn’t done that one if I’d a knowed it would make him feel that way.

He has come far in his moral education; when he first realized that Jim was a runaway, he was torn between the conventional thought that he owed it to Miss Watson to restore her “property” to her, and his understanding of Jim’s desire to be free and re-united with his family. It is hard not to wish that Tom Sawyer could have undergone such a moral transformation before playing thoughtlessly cruel practical jokes on Jim at the end of the book.

And yes, Tom Sawyer’s arrival on the scene does dissipate most of the interest that the story has for readers. Even so, Tom is instructive as a foil to Huck. He calls attention to Huck’s best qualities by his own notable lack of them. That is, Tom lacks the empathy, insight, and charity that Huck possesses in abundance, and that are the reason why most readers have, long before the end of the book, come to regard Huck as a hero.

N&C criticizes Twain for saying, in effect, that white people can make up for the injustices that they have committed against blacks by cultivating kindly feelings toward them. To which I would answer that kindly feelings are not enough, of course, but neither are they to be despised.

For almost a century, black Americans would be stifled in all their aspirations by violence and the ever present threat of violence; and even at the end of this terrible time, most black Americans would continue to receive frequent reminders to stay in their places — the places having been defined by white people. Stowe could appeal directly to the elemental sense of justice in white people; Twain could not make any such direct appeal. So Twain beguiled his audience into being morally educated vicariously, through the moral adventures of a young boy. And if the only fruit of this education was kindly feelings, that at least was a start. The day would come when the kindly feelings of white people could no longer accept the segregation of blacks from the mainstream of our national life.

The compelling interest and importance of the issues touched upon in Mark Twain’s great book are enough almost to make readers overlook the sense of beauty that suffuses it — the beauty of youth and life, but above all the beauty of nature, especially of the magnificent Mississippi River. Bearing witness to a thunderstorm from the vantage point of a cave on Jackson Island, Huck shows himself to be one of our country’s greatest nature poets — greater, for my money, than Emerson or Thoreau:

Pretty soon it darkened up, and begun to thunder and lighten; so the birds was right about it. Directly it begun to rain, and it rained like all fury, too, and I never see the wind blow so. It was one of these regular summer storms. It would get so dark that it looked all blue-black outside, and lovely; and the rain would thrash along by so thick that the trees off a little ways looked dim and spider-webby; and here would come a blast of wind that would bend the trees down and turn up the pale underside of the leaves; and then a perfect ripper of a gust would follow along and set the branches to tossing their arms as if they was just wild; and next, when it was just about the bluest and blackest—fst! it was as bright as glory, and you’d have a little glimpse of tree-tops a-plunging about away off yonder in the storm, hundreds of yards further than you could see before; dark as sin again in a second, and now you’d hear the thunder let go with an awful crash, and then go rumbling, grumbling, tumbling, down the sky towards the under side of the world, like rolling empty barrels down stairs—where it’s long stairs and they bounce a good deal, you know.

“Jim, this is nice,” I says. “I wouldn’t want to be nowhere else but here. Pass me along another hunk of fish and some hot corn-bread.”

I particularly agree about Twain’s purposes in writing this book in this way being misunderstood, intentionally or not, by a good many people over the years and, by the way, your “N&C”, who should know better and perhaps does, can go straight to the place in hell postulated by Huck that was never filled by him. Our own age is no exception to the censoriousness provoked by this book since its publication, with portions of both the political right and left deploring its existence and wanting to remove it from public bookshelves or, at least, to make access to it as difficult as possible.

I hope that the book eventually flourishes again thanks to people who have the wisdom to take in a beautifully-written tale about the moral education of a boy who through various trials chooses to remain true to his own good self.

LikeLike

John, I really enjoyed this essay. HF is a book I taught so often over the years th

LikeLike

Glad you liked it. I’d like to hear about your experience teaching HF. I never had the privilege.

LikeLike