Note: This post introduces a feature called Spotlight on Neglected Worth that will appear from time to time on this site. Most articles posted under this rubric will be shorter than the other posts.

I used to believe that Time, the only literary critic whose opinion really matters, would take care to preserve the works of all worthy writers and ensure that they remain known to posterity. Lately, I’ve been seeing evidence that Time performs this important function less diligently than I had imagined. Take the case of Conyers Middleton (1683 — 1759).

Even if you know your way around in the age of Alexander Pope (1688 — 1744), chances are you haven’t heard of Middleton. I discovered him in a footnote in an edition of Pope’s Dunciad (a rollicking work in which Pope fries his enemies in the crackling hot oil of his wit). The footnote says that Pope regarded Middleton as the only person in England who wrote prose as distinguished as his own. (Pope later quarreled with Middleton and never had a nice thing to say about him after that.). As distinguished as his own? That is high praise indeed. Pope’s introduction to his own translation of the Iliad, for example, is one of the greatest essays in the English language, combining critical insight with urbanity of manner and forcefulness of expression. That is my opinion — and Pope’s.

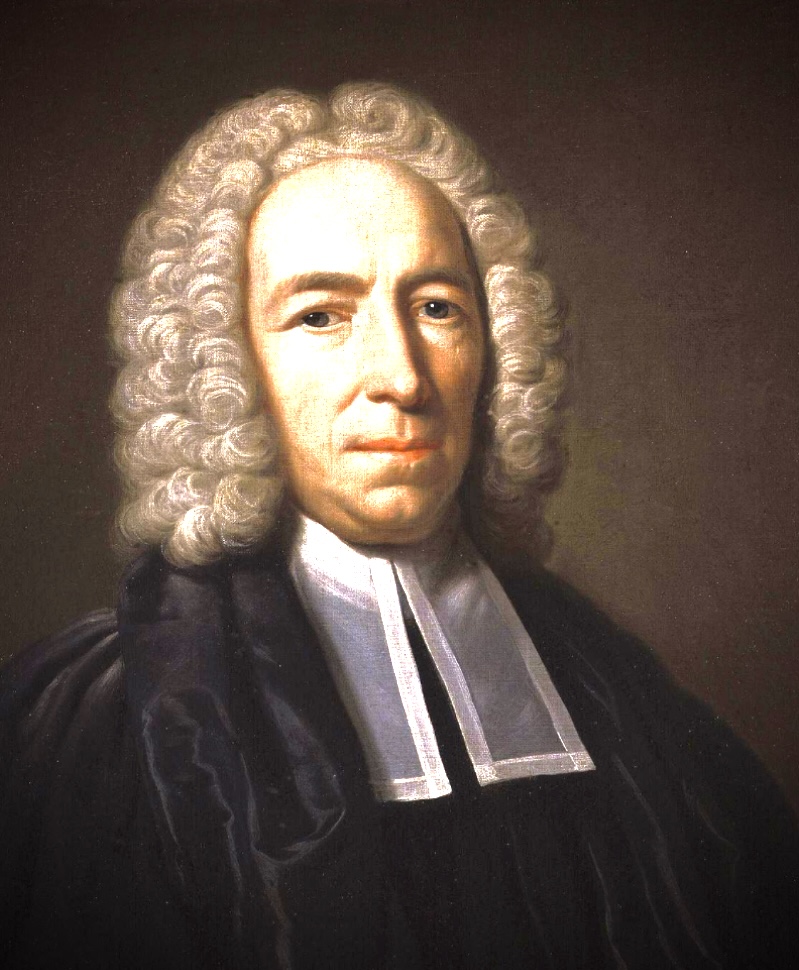

Conyers Middleton was a clergyman from Yorkshire who would have been entirely devoured by oblivion were it not for Pope’s praises, noted above, and for his authorship of a biography of Marcus Tullius Cicero ( 106 — 43 B.C.), the ancient Roman orator and statesman. The biography of Cicero was a well deserved success, in spite of the accusation that it incorporates a great deal of material from the work of another writer. The accusation is true, but Middleton rewrote whatever he stole in his own exemplary style. I’m not sure, then, where that leaves the accusation of plagiarism. Middleton would have done well, at least, to acknowledge the other writer’s contribution to his own work, but he did not.

Middleton begins his biography of Cicero with the following statement of purpose:

TH ERE is no part of history, which seems capable of yielding either more instruction or entertainment than that which offers to us the select lives of great and, virtuous men, who have made an eminent figure on the public stage of the world. In these we see at one view, what the annals of a whole age can afford, that is worthy of notice, and in the wide field of universal history, slipping as it were over the barren places, gather all its flowers, and possess ourselves at once of every thing that is good in it.

Middleton here restates, in his elegant manner, the ancient commonplace that history is valuable chiefly as the record of the deeds of great men, whose virtues are to be studied and emulated. This school of history has had a few modern practitioners, such as John F. Kennedy in his charming study Profiles in Courage. There have been fewer modern historians to share Middleton’s admiration of Cicero himself.

In the following passage, Middleton describes his debt as an historian and biographer to the very man about whom he is writing:

In the execution of this design, I have pursued as closely as I could that very plan which Cicero himself had sketched out for the model of a complete history. WHere he lays it down as a fundamental law, that the writer should not dare to affirm what was falsse, or to suppress what was true ; nor give any suspicion either of favour or disaffection : that in the relation of facts he should observe the order of time, and sometimes add the description of places ; should first explain the counsels, then the acts, and lastly the events of things : that in the counsels he should interpose his own judgment on the merit of them; in the acts relate not only what was done, hut how it was done ; in the events show what share chance or rashness or prudence had in them; that he should describe likewise the particular characters of all the great persons who bare any considerable part in the story; and should dress up the whole in a clear and equable style, without affecting any ornament or seeking any other praise but of perspicuity.

This paragraph encompasses a great deal of matter without confusion or obscurity; the individual points are made separately and distinctly; there is an easy flow from point to point; and the rhythm of the whole is pleasing.

It is unlikely that there will ever again be an audience for what Conyers Middleton has to offer — the rhetoric of the British educated classes in the eighteenth century, freed of its laboriousness and pomposity. But once there was such an audience, to Britain’s great credit.

You probably won’t seek to deepen your acquaintance with Conyers Middleton, unless you are interested in Cicero or eighteenth century English literature, and that’s OK. You have joined me in bearing witness to Conyer Middleton’s limited, specialized, and very real excellence.

I had not heard of him.

I’m always amazed to see the subtle differences in phrasing and sentence structure that can transport you back in time.

I wonder what it is in the brain that process that to give the reader such context or opinion of the author?

and I get a new word…perspicuity!

LikeLike

An excellent point — style can transport you back in time. When I read 18th century prose, I feel that I’m in a world that is stable, sane, and sure of itself. A refreshing change of pace. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike

The dog ate my homework, which is to say that a dropped connection absconded with the comment I was about to post — worthy of Pope, you may be sure — so I’ll just quickly note that what Conyers and others before and after him were able to do with English was simply astonishing. It’s astonishing to me, anyway, how they could write whole books filled with long, complex sentences of great beauty and clarity in a language that’s weakly inflected and crazily patchworked in origin. We’re all lucky that the printing press and then digitization has preserved so much of the Great Age of English. (So says an oldster living in the Great Age of Subscription Television.)

LikeLike

Quite so. I flipped to the back of the Cicero bio to see whether Middleton could tell a story in that wonderful style of his. The story would be how Cicero tried to escape from Marc Anthony’s hit men. (They got him.). Middleton told it well, bringing out the suspense and the horror.

LikeLike

I studied 18th C British in my masters program and don’t recall ever hearing of Mr. Middleton. But anyone who correctly uses perspicuity in a sentence (my autocorrect wanted to change that to perspicacity) gets my vote.

LikeLike

I’d never heard of him, either. His book on Cicero is excellent, apart from the fact that it’s about Cicero.

LikeLike