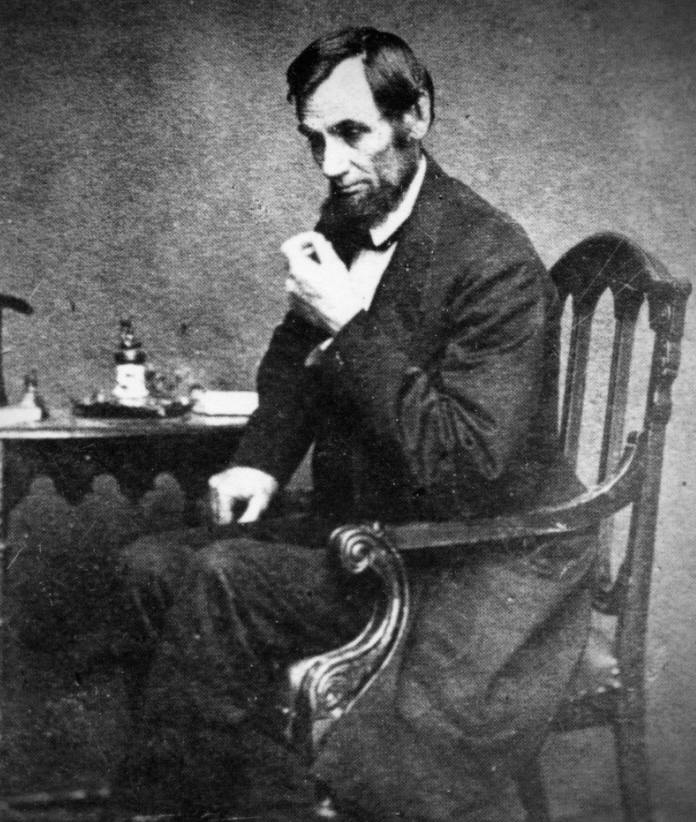

Several of my most devoted — and, need I say it, most discerning — readers have told me that they like to read about Lincoln in this space. I am loathe to disappoint them. And it happens that I like to write about Lincoln. So I will now revisit the subject, which, I am happy to find, is inexhaustible.

In this post, I will look at a public letter that Lincoln wrote to Horace Greeley, the founder and editor of the New York Tribune, on August 22, 1862. Greeley was a leader of the faction of the Republican party that wanted Lincoln to take immediate action against slavery. Lincoln wrote to reassure Greeley that he had not forgotten about slavery, the cause of the war; while doing this, he had to be careful not to alarm the faction of the party that insisted that the war was fought to preserve the Union and with no other aim. Lincoln wrote at a time when the war was not going well for the North and enlistments were not supplying the needs of the Union army. While failing to pacify the passionate and irascible Greeley altogether, Lincoln’s letter was widely admired for its vigorously reasoned exposition of his policies, and for its kindness and tact in dealing with Greeley.

Lincoln’s letter was in response to an editorial that Greeley had written and published in the Tribune on August 20. Titled “The Prayer of Twenty Million”, it criticized Lincoln for not enforcing the Confiscation Acts passed by Congress and signed by Lincoln in 1861 and 1862. These acts required Union forces to confiscate confederate property, including slaves, whenever possible. Lincoln‘s enforcement of these laws was deliberately lax; he was not yet ready to make such a direct attack on slavery..

One hundred years later, Robert Penn Warren would write that the Civil War happened because the South over-estimated how much the North cared about blacks and under-estimated how much it cared about the Union. Lincoln made no such miscalculation. He knew that northern soldiers believed themselves to be fighting to preserve the Union, not to emancipate the slaves. He knew that the border states — Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware — might join the South if the war became a war of emancipation. And he feared that resistance to a draft, which he expected in any case, would be far greater if he were drafting men to liberate slaves.

The mood of Lincoln’s critics is exemplified by this letter that Horace Greeley sent to Senator Charles Sumner on August 7, 1862:

My dear sir:

Do you remember that old theological book containing containing this

”Chapter I. Hell.

Chapter II. Hell Continued.”

Well that gives a hint of the way Old Abe ought to be talked to in this crisis in the nation’s destiny.

The drift and tenor of Greeley’s “Prayer of 20 Millions” can be inferred from these excerpts:

- We think you are strangely and disastrously remiss in the discharge of your official and imperative duty with regard to the emancipating provisions of the new Confiscation Act.

- We think you are unduly influenced by the counsels, the representations, the menaces, of certain fossil politicians hailing from the Border Slave States.

- We think timid counsels in such a crisis calculated to prove perilous, and probably disastrous.

- We complain that the Union cause has suffered, and is now suffering immensely, from mistaken deference to Rebel Slavery.

- We complain that the Confiscation Act which you approved is habitually disregarded by your Generals, and that no word of rebuke for them from you has yet reached the public ear. . . I entreat you to render a hearty and unequivocal obedience to the law of the land.

Here is Lincoln’s public letter to Greeley:

Executive Mansion,

Washington, August 22, 1862

Hon. Horace Greeley:

Dear Sir.

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive l”it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing anyslave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.

Yours,

A. Lincoln!

This letter is extraordinary in several respects.

It is extraordinary in having been written at all. “So novel a thing as a newspaper correspondence between the President and an editor excites great attention,” wrote one journalist. No all of the attention was favorable. Many people, including some of Lincoln’s supporters, felt that for Lincoln to respond to criticisms printed in a newspaper would diminish the dignity and effectiveness of the office of president.

It is extraordinary in the boldness with which it refuses to answer Greeley’s criticisms point by point. Not wishing to antagonize so influential a supporter, or to impair the dignity of the presidency by arguing with a newspaper editor, he disposes of Greeley’s erroneous statements and false inferences by an adroit use of the rhetorical device praeteritio, in which the speaker or writer calls attention to a fact by announcing that he is going to ignore it. (“If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them.”)

It is extraordinary for the magnanimity of its treatment of Greeley. Lincoln writes: “If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.” The magnanimity of Lincoln’s “deference” to Greeley as an old friend strikes me as genuine.

[Lincoln was hardly the only person to be handled roughly by Greeley. Once Mark Twain mistakenly entered Greeley’s office while looking for someone else in the same building. Greeley, looking up from his work, said to Twain, “Whoever you are, get the hell out of here!”. Twain said, “I’m just looking for a gentle_” “We don’t have any of those in stock here!” Greeley interjected. This was Mark Twain’s sole meeting with Greeley.]

Lincoln believed — this is my guess — that there was something wrong with Greeley, as does a modern biographer, who thinks that he had Asperger’s Syndrome. And Lincoln liked to make allowances for people whose personal problems or defects forced them to engage with the world at an oblique angle. He had chosen as his law partner the eccentric, hard drinking, politically radical William Herndon; their partnership lasted for 16 years. He had special affection for his son Tad, whose pronounced lisp caused him social problems and emotional turmoil. He invited a fellow Springfield lawyer, the large and loutish Ward Hill Lamon, to accompany him to Washington as a bodyguard and factotum; the detective Allen Pinkerton, who foiled at least one assassination attempt on Lincoln, said that Lamon was “an idiot.” (Lamon was out of town on official business the night of Lincoln’s assassination.) So I find it easy to suppose that Lincoln’s deference to Greeley was based on a sort of affection — only note that it is Greeley’s heart, not his mind, that Lincoln supposes to to be right.

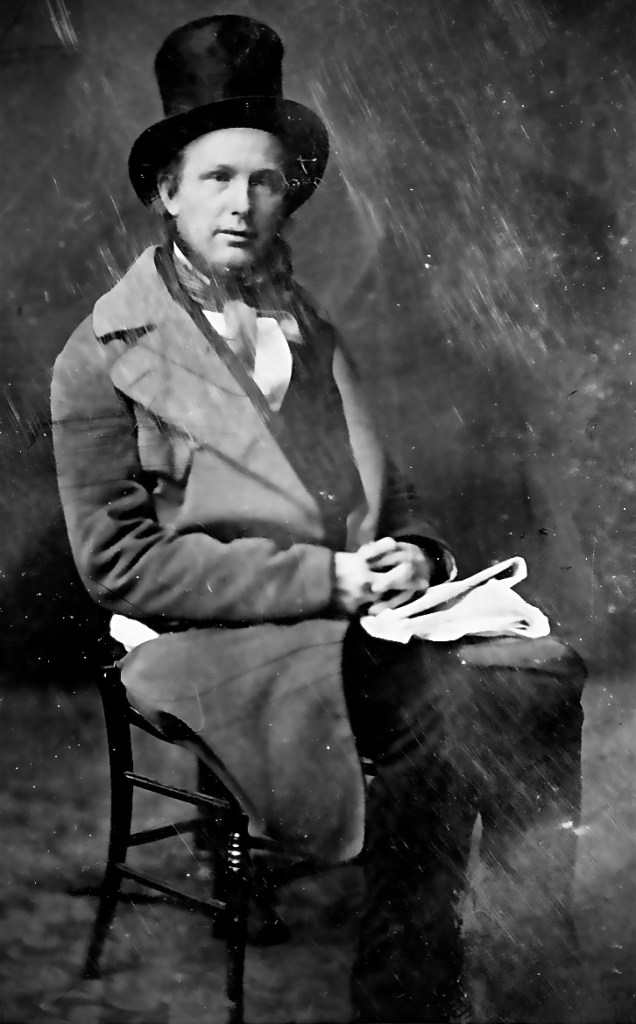

Lincoln also no doubt respected Greeley for his strengths and accomplishments. Like Lincoln, he had made his way upward in the world through hard work and ability. His family lost everything in the panic of 1837, and he was forced at age 15 to leave school and apprentice himself to a printer in Vermont. Here he learned the technical and business side of the newspaper business. He then moved to New York City, which at that time supported dozens of daily papers. For several years he took small writing and editing jobs for various papers, and then founded The New-Yorker, a weekly which, like its unhyphenated twentieth century namesake, reported literary and artistic news for a sophisticated audience. When Greeley’s New-Yorker failed (James Thurber would not be born until 1894), he founded a newspaper that he named The Tribune, and saw to it that that it was well-edited and written. (Among his talented writers and editors was Margaret Fuller, through whom he became acquainted with a remarkable young writer in Concord, Massachusetts named Henry David Thoreau; Greeley would tirelessly promote Thoreau’s writing for the rest of his short life.) The Tribune quickly achieved the largest circulation of any newspaper in the country, largely through mail subscriptions, which made it a truly national newspaper.

Greeley’s political history was like Lincoln’s as well. He became an energetic supporter of the Whig Party (like Lincoln), and when the Whig Party was destroyed by sectional tensions, he migrated to the Republican Party (like Lincoln). He was unlike Lincoln, however, in his uncompromising advocacy of the abolition of slavery, of women’s rights (including the right to vote) , of the rights of indigenous people, and various other reforms. He became a political ally of prominent New York Republicans such as William Seward and the powerful party boss Thurlow Weed.

Lincoln, then, had reasons to pay Greeley deference, but the rest of his letter does not address Greeley’s criticisms at all. In fact, Lincoln had written a draft of it before Greeley published his editorial.

Finally, this letter is extraordinary for its extreme lucidity. In writing the letter, Lincoln had evidently taken extraordinary pains to make his meaning unmistakable. He systematically anticipates every possible misinterpretation of his motives and counters each one with his actual position. It is as good an example as any of the impassioned reasoning that is the basis of his eloquence. Given the important purposes that this letter was to serve, it was natural that Lincoln should wish it to be understood correctly.

The speech by Lincoln that most resembles this letter in its painstaking striving after unmistakable meaning was the Cooper Union Address, delivered in New York City on February 27, 1860. In that speech, Lincoln presented a tightly reasoned argument that the United States Constitution gave the Congress the power to regulate slavery in the territories — and even to exclude it. The speech made Lincoln a leading contender for the Republican nomination. Please see Sam Watterston’s remarkable recreation of that address:

https://www.c-span.org/video/?181864-1/abraham-lincolns-cooper-union-address

But in fact, Lincoln had been working at the art of making his meanings unmistakable since his youth. When he was a child he liked to listen to conversations between adults, but he became frustrated and angry whenever he could not understand what the adults were talking about. This experience accounts, some think, for what became in him a passionate concern for clarity of expression. Just as he hated to be baffled, he hated to baffle others.

What was the political value to Lincoln of this letter?

In answering Greeley’s letter, Lincoln was able to address not only the public, which needed assurance that Lincoln had a plan. It also addressed the vehemently anti-slavery wing of the Republican Party, which had been growing restive as months passed without progress being made to destroy slavery. In the letter, Lincoln stated several times, that he would attack slavery directly if he thought that this would further the primary aim of the war, the restoration of the Union. What he did not reveal is that he had already written a draft of a “preliminary emancipation proclamation.”. He had decided not to release the proclamation, however, until a Union army had won a significant victory over the south; otherwise, releasing the proclamation might appear to be an act of desperation.

He did not have to wait much longer. On September 17, 1862, the main Union army, led by general George McClellan, fought Lee’s army at a place known as Antietam, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Each army suffered such extreme casualties that talk of a victory seemed absurd. Lee was, however, forced to withdraw his army from Maryland.

Several days after the battle, when the nation was still trying to comprehend the scope of the horror at Antietam, Lincoln called a meeting of his cabinet. As he often did, he began the meeting by reading out loud the latest newspaper column by Artemus Ward, his favorite humorist:

IN the fall of 1856 I showed my show in Utiky, a trooly grate sitty in the State of New York.

The people gave me a cordyal recepshun. The press was loud in her prases.

1 day as I was givin a descripshun of my Beests and Snaiks in my usual flowry stile, what was my skorn & disgust to see a big burly feller walk up to the cage containin my wax figgers of the Lord’s Last Supper, and cease Judas Iscariot by the feet and drag him out on the ground. He then commenced fur to pound him as hard as he cood.

“What under the son are you abowt?” cried I.

Sez he, “What did you bring this pussylanermus cuss here fur?” & he hit the wax figger another tremenjus blow on the hed.

Sez I, “You egrejus ass that air’s a wax figger—a representashun of the false ’Postle.”

Sez he, “That’s all very well fur you to say, but I tell you, old man, that Judas Iscariot can’t show hisself in Utiky with impunerty by a darn site!” with which observashun he kaved in Judassis hed. The young man belonged to 1 of the first famerlies in Utiky. I sood him and the Joory brawt in a verdick of Arson in the 3d degree.

The members of Lincoln’s cabinet enjoyed the story although Stanton thought that such a frivolous diversion was not appropriate given the somber circumstances. Then Lincoln brought out his draft of a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and read it to the cabinet. He had decided to make this proclamation public on September 22, he said. Antietam, terrible as it was, was a victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclsmation is far from his most eloquent composition — in fact, he appears to have made it prosaic deliberately — one paragraph is as stirring as anything he ever wrote:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free . . .

.

I’ve read Lincoln’s letter before, but the context supplied by this essay convinces me that the letter remains one of Lincoln’s best. As you said, each potential avenue of counter-argument was cut off in advance by Lincoln’s logic, and the letter succeeds politically and substantively. A couple of observations. First, I noticed again that Lincoln uses the conditional mood, present tense with precision (“… if there be any inferences …”). This precision barely exists in American English today. Second, I would nominate Secretary of War Edwin Stanton as an additional misfit in Lincoln’s life; Stanton was socially maladroit to a point that abutted misanthropy. That Lincoln tolerated the frequent outbursts and general choler of the man is remarkable to me.

LikeLike

Yes, the letter became famous and helped Lincoln politically. Man, the son-of-a-gun could write!

LikeLike