I once spent a summer evening, around fifty years ago, sitting on the porch of a house I was staying in, seeking relief from smothering heat. For company I had a bookish acquaintance — not quite a friend — and we were trying to come up with a short list of the true and indispensable masterpieces of American literature. We felt fully qualified for this task; we were young. I forget what we thought we could do with the list.

We made the obvious choices — Huckleberry Finn, Moby Dick, Leaves of Grass, and plenty of Emily Dickinson — and then stopped to think whether we had missed anything that could compare with these works. We thought and thought — and thought. Finally I said, “What about Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address?”

My acquaintance was surprised by this suggestion. He didn’t know much about Lincoln and had never read the address. But he wanted to know why I had thought of it — a speech, of all things. I went into the house and got a book that I knew included the text of the address. Back on the porch, I read it out loud, slowly and carefully. Here is the full text — I recommended that you read it out loud yourself:

Fellow-Countrymen:

At this second appearing to take the oath of the Presidential office there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first. Then a statement somewhat in detail of a course to be pursued seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of this great conflict which is of primary concern to the nation as a whole, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself, and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh." If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achievel and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations

When I finished reading it, we were both stunned. We felt that we had just heard, not a speech, but a great musical composition, with the four paragraphs representing different movements. The first two movements were slow, deliberate, and measured; the third movement, by far the longest, was marked by slowly increasing emotional intensity; the fourth movement was a grave and majestic resolution of the whole.

This was our impression. As I said, we were young, and we had been trying to cool ourselves down with Budweisers all evening. But even today, I find that The Second Inaugural Address, of all Lincoln’s writings, is uniquely suggestive of music.

But it is music made of words and their meanings, and of the context in which those words were spoken. The speech becomes even more remarkable the more you look into the meaning and context of its words.

Lincoln was inaugurated for a second term as President on March 4, 1865. The armies of the Confederacy had by then been worn down by battle, disease, and desertion until they were incapable of fighting any longer. Lee would not surrender the principal Confederate army for another five weeks, but the outcome of the war was not in doubt. In the meanwhile, tens of thousands of sick and wounded soldiers, both Northern and Southern, were suffering private hells in makeshift military hospitals scattered across the thousand mile wide theatre of war.

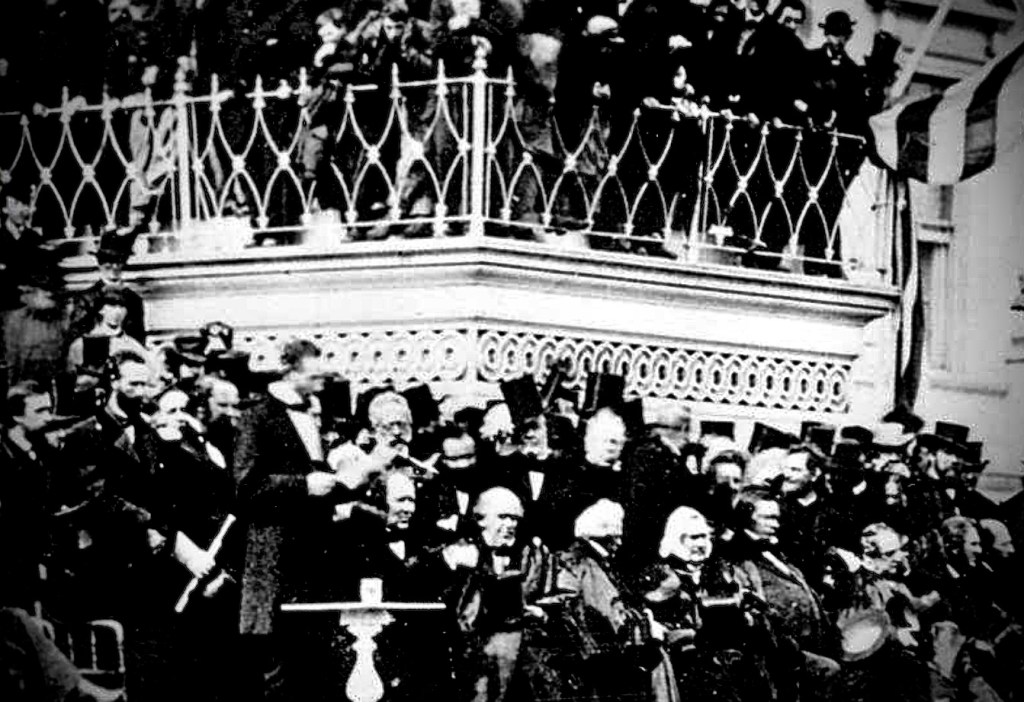

A photograph exists of Lincoln delivering his Second Inaugural Address. In this photograph, his head is bent forward slightly as he reads the address from papers in his hands. His unusual height is apparent; he truly was a physical anomaly. In front of him is a stand on which someone had placed a glass of water. (The stand was for some years in the possession of the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston. I went to see it one day — to be in the presence of an object that had stood in the presence of Lincoln as he delivered his address, and that had held the glass of water from which he drank. When I got to the Society, I found out that the stand had been sent to the national archives in Washington a few days before.)

The crowd at Lincoln’s second inauguration was much larger than the crowd at his first. It is safe to say that people had come to hear a victory speech. Lincoln could have been pardoned for giving one. Under his leadership, the North had achieved what few had thought possible four years earlier. The Union was saved, democracy was vindicated, and slavery was soon to be abolished. As Bismarck and leaders of other nations realized, with the victory of the North a world power of the first rank had been created. Lincoln had accomplished something greater even than Washington had accomplished.

But only the people standing within a few yards of Lincoln were able to hear his words, which were as remarkable as his achievements. “Fellow countrymen”, he began, addressing the people both of the North and of the South. He continued, in a dry matter of fact tone, to recapitulate how the war had started, noting that the South had started it — as close as he was to come to criticizing the South in the entire address: “Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.”

The third paragraph of the speech is by far the longest. I do not feel that I am engaging in hyperbole when I say that it is a masterpiece of thought and expression.

First the thought. Lincoln meditates on the crime of slavery and the will of God, Who, Lincoln says, held both North and South accountable for that crime, giving to both the war as its punishment. An astonishing conclusion to have been reached by the leader of the victorious armies! Lincoln is said to have disliked “The Battle Hymn of the Republic”, which he regarded as self-righteous; he preferred the unpretentious song “Dixie”, which he said the North could claim as booty of war.

[Lincoln’s refusal to enlist God under the Union banner makes him somehow similar in conviction to Karl Barth (1886 – 1968) who is widely regarded as the greatest protestant theologian since Calvin. Barth insisted that God is not immanent in the human mind or human heart but is “above him—unapproachably distant and unutterably strange,” “unknown,” “Wholly Other” (Rom. II, 27, 56, 49). Barth became interested in the American Civil War after someone gave him books about it as a present; he even asked to be taken on a tour of the Gettysburg battlefield during one of his few visits to the United States. I can imagine that he would find much to approve in the Second Inaugural Address, but I have been unable to find that he ever had anything to say about Lincoln or his ideas about God.]

Next, the expression. The language of this paragraph resounds with the cadences of the Authorized or King James Version of the Bible — so much so that Lincoln could easily and naturally incorporate Matthew 18:7–14 (“Woe unto the world . . .”) and Psalm 19:9 (“The judgements of the Lord l . . “) from that version into his own words. Lincoln’s mastery of the spoken word is nowhere better exemplified than in this paragraph, with its slowly increasing emotional intensity, reaching a crescendo with the quotation of Psalm 19:9.

The final paragraph makes no distinction between North and South in calling upon Americans to work together to restore the Union. Lincoln had for some time been looking forward to the problems of reconstruction. He knew how damaged and exhausted the country was, how little remained of its stores of generosity and idealism. But there was the work of healing to be done.

One of the first people to comment on address was Frederick Douglass, who told Lincoln at a White House reception after the inauguration that it was a “sacred effort”. Thurlow Weed, the Republican party boss of New York, wrote Lincoln a letter praising the speech. Lincoln’s reply is well known:

Thurlow Weed, Esq

My dear Sir.

Every one likes a compliment. Thank you for yours on my little notification speech, and on the recent Inaugeral [sic] Address. I expect the latter to wear as well as — perhaps better than — anything I have produced; but I believe it is not immediately popular. Men are not flattered by being shown that there has been a difference of purpose between the Almighty and them. To deny it, however, in this case, is to deny that there is a God governing the world. It is a truth which I thought needed to be told; and as whatever of humiliation there is in it, falls most directly on myself, I thought others might afford for me to tell it.

Yours truly

A. LINCOLN

The Second Inaugural Address prompted Walter Bagehot, the brilliant editor of the London Economist, to write a generous palinode in an editoral published on the occasion of Lincoln’s death. For the previous four years, Bagehot had been writing articles about American affairs, and in all that time had found nothing better to say about Lincoln than that he was “well-meaning” and “honest”. Now he wrote:

We do not know in history such an example of the growth of a ruler in wisdom as was exhibited by Mr. Lincoln. Power and responsibility visibly widened his mind and elevated his character. . . .The very style of his public papers altered, till the very man who had written in an official dispatch about “Uncle Sam’s web feet” drew up his final inaugural in a style which extorted from critics so hostile as those of the Saturday Reviewers a burst of involuntary admiration. . .

In 1963, the American theologian and political activist Reinhold Niebuhr wrote, with reference especially to the Second Inaugural Address, that

the religion of Abraham Lincoln in the context of the traditional religion of his time and place … must lead to the conclusion that Lincoln’s religious convictions were superior in depth and purity to those, not only of the political leaders of his day, but of the religious leaders of the era.

What do I make of all this?

The democracy to which Lincoln devoted his life would now seem to have fallen on very hard times, so hard that a recovery seems almost impossible. The appearance of Lincoln in our history — improbable in the extreme as it was— can provide us with comfort, the comfort of knowing that we may not appreciate, in our moments of dejection, just how rich in possibility is the realm of the actual. But much is demanded of us. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln urged us to be devoted to “the task remaining before us”, the task of winning the war for democracy . In his Second Inaugural Address, he urged us to “bind the nation’s wounds”, that is, the wounds of a nation that was divided and horribly damaged. When asked to take up such tasks, we very naturally hesitate, in view of their difficulty. But, on the other hand, can we really consider refusing? It is Abraham Lincoln who is asking . . .

Thank you for calling our attention to this 2nd inaugural address. Such weight in Lincoln’s words. It will always be a wonder where Lincoln’s prose came from, the metrics under his thoughts. but it’s an astonishment nonetheless.

LikeLike

Old friends of the Lincolns remember his mother, Nancy Hanks, as being intellectual and brilliant. I am guessing the Abe good some good qualities from her.

LikeLike

A compliment for you, John Frederick, for this post especially, among so many others.

I keep thinking, post after post, that you’ve outdone yourself. Now this.

Lincoln’s words in context are a marvel.

Thank you for reminding us of that by setting the historical context so scrupulously

and then by extending it in your own conclusion to our frayed and nearly fractured present.

It’s a thrilling read, all of it.

LikeLike

Glad you liked it. I got out my pocket calculator and found that on average one American president out of every 46 is a literary genius. We may have to wait a while for another Lincoln.

LikeLike

Yes, there are echoes in Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address of the greatest extended prose work (neither play nor verse) in English, the King James Version of the Bible which was, to be fair, a collaborative effort. That’s my opinion only, of course; some contents may have settled during shipping and handling. What a piece of persuasion Lincoln wrote! In an age of liquified offerings from professional speechwriters, it’s even more marvelous to contemplate. As to your observations about our own time, I know that for many our predicament might seem to be beyond retrieval — the forces of reaction haven’t been this strong since the Civil War — but I try to remember that a solid majority of Americans still believe in democracy and the rule of law.

LikeLike