I suspect that most of my friends and acquaintances do not believe that there is a second order of existence apart from this present one in which we are born, work, pay taxes, and die. There may not be. Very likely there isn’t. But I at least wish that there were such an order.

I am a reluctant unbeliever. When I read the Sermon on the Mount, or the parable of the Good Samaritan, I cannot help feeling that this teaching must have a source outside this quotidian order of things.

But my faith —or aspiration toward faith — stumbles over the Immaculate Conception, the Virgin Birth, and the Resurrection. And I don’t need any help from Hume to doubt miracles.

All this means that I am left with two choices: either to stop thinking about ultimate questions, or to adopt a faith in something provisionally, undogmatically, hopefully, doubtfully. Not thinking is easy; the immediate demands of daily life almost require it. But sometimes, in quieter moments, I can’t stop thinking about ultimate questions, and there I am: a provisional, undogmatic, hopeful, and doubtful something or other.

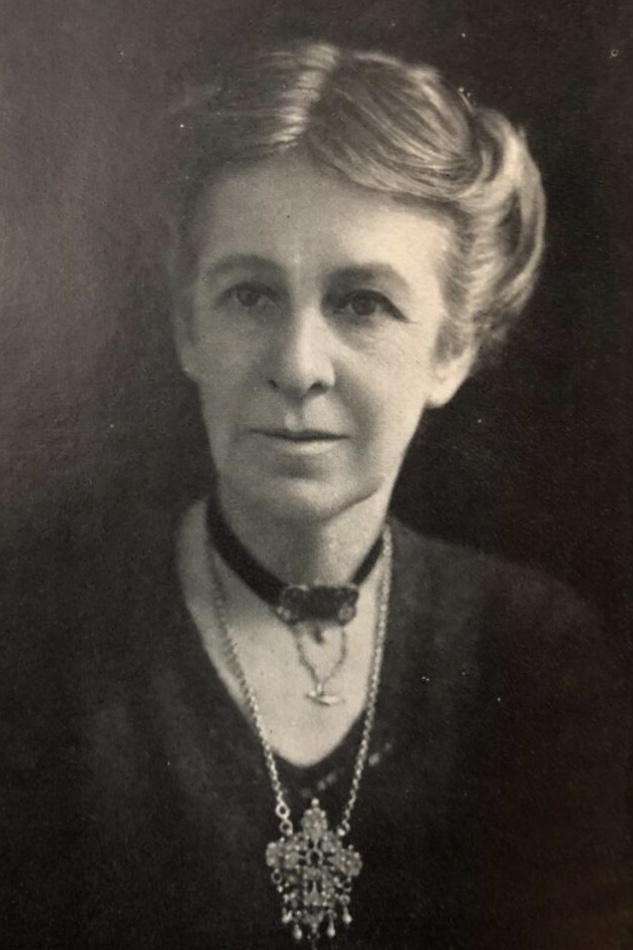

In such mood, I often turn to the writings of Evelyn Underhill (1875 -1941), an Anglican authority on mysticism and prayer. In her best known book Mysticism (1911), she wrote

A direct encounter with absolute truth, then, appears to be impossible for normal non-mystical consciousness. We cannot know the reality, or even prove the existence, of the simplest object: though this is a limitation which few people realize acutely and most would deny. But there persists in the race a type of personality which does realize this limitation: and cannot be content with the sham realities that furnish the universe of normal men. It is necessary, as it seems, to the comfort of persons of this type to form for themselves some image of the Something or Nothing which is at the end of their telegraph lines: some “conception of being,” some “theory of knowledge.” They are tormented by the Unknowable, ache for first principles, demand some background to the shadow show of things.

For better or worse, modern life distracts us from seeking “a direct encounter with absolute truth” and for most people this is a very good thing. The person who has had such an encounter can easily forget that they are still human, that is, a quite shabby disreputable sort of being. Among the side effects of mystical experience is megalomania; Walt Whitman, for one, did not entirely evade it. Our culture, being largely unacquainted with mystical experience, has no tried and assured disciplines to offer the mystic to keep him from distressing (to others as well as to himself) experiences.

One thing I try to remember when reading Evelyn Underhill: she is not, for the most part, writing about the psychology of religion. She is not advocating the cultivation of that self-referential mess called “spirituality”. She is writing about the objective existence of the Other, which is the “background of the shadow show of things.”

So what do I get out of reading Evelyn Underhill? Certainly the pleasure of reading her distinguished prose — but anything more? Perhaps it is simply a desire to keep alive in myself the instinct that knows the world to be derivative, deceptive, and stale. For whenever I start to find it bright, original, and absolute, then I will know that my nature has been subdued to what it works in like the dyer’s hand. And that would be a pity.

Underhill — as evidenced by the short quotation here — writes beautifully. I take nothing away from her when I say that she fails to answer the very question that everybody else who’s ever lived has failed to answer. Hamlet put the question pretty well, it seems to me. At long last I’ve come to the realization that, when considering this topic, I’m as much at-sea as the next fellow, so we might as well get on with the swimming and not drown in anxiety and dread, as Lucretius reminded us.

LikeLike

I think that EU was writing more about longing than anxiety or dread. “il faut cultiver son jardin” is far from contemptible as a piece of advice. For some people, though, it will not do.

LikeLike

I think that longing, anxiety, and dread are all facets of uncertainty, but that’s definitely my own perception, as is the thought that equanimity in the face of all this is the most difficult state of mind for a human being to achieve.

LikeLike