Incredibly, the classic stories of James Thurber are no longer the several decades old that they were when I first got to know them. They are close to a century old. This monstrous fact does not take from them any of their freshness, however. They live by their truth. And their truth is the tragic and painful truth of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, transposed into comedy.

Thurber was not a happy man. His unhappiness made him rather cruel; his cruelty destroyed his marriages; and the failure of his marriages made him unhappy. The irony of all this did not escape his attention.

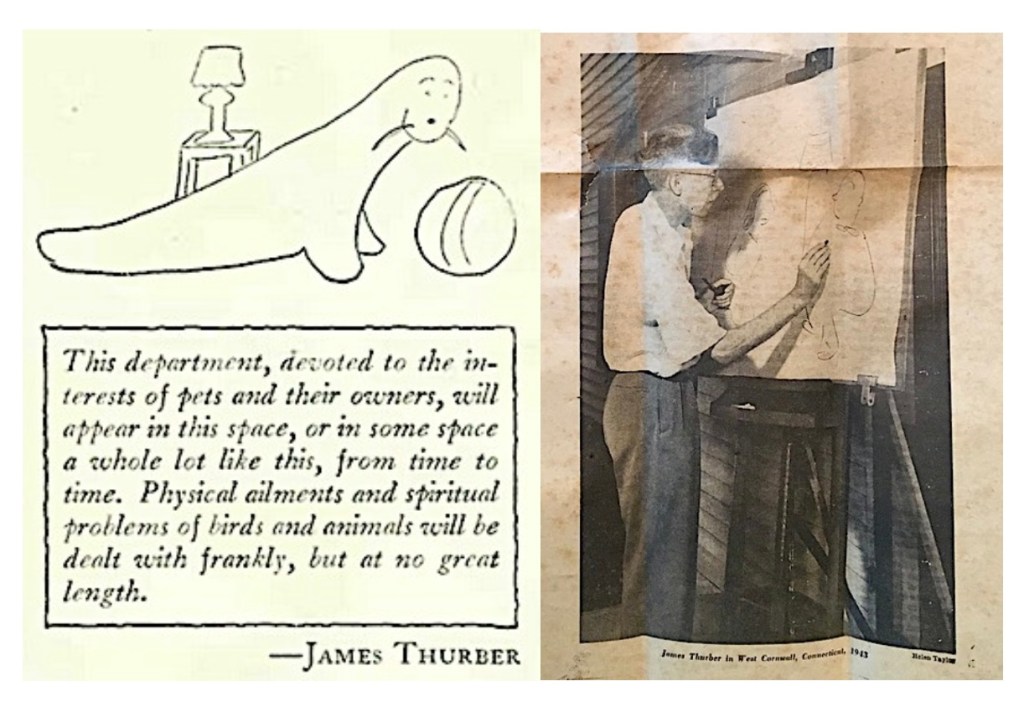

In the small cramped office at the New Yorker magazine that he shared with the saintly E. B. White, Thurber began to commit his despair to paper, drawing pictures of people contending with their daily embarrassments and humiliations — and in the case of men and women together, contending with each other. Thurber was blind in one eye and was rapidly losing sight in the other. His drawings consisted of wild loops suggesting masses of flesh in motion and short deft strokes that captured the essence of the souls of men and women in the throes of bewilderment.

Because Thurber drew only to relieve his own misery, he saved nothing. Instead, he crumpled the paper on which he had drawn, and threw the crumpled paper into his waste basket. E.B. White, however, believing that no product of Thurber’s troubled imagination could be without interest, started to fish Thurber’s crumpled sketches out of the wastebasket. He smoothed the paper flat, inked in the penciled lines, and either asked Thurber to supply captions or supplied captions himself.

White then showed the inked-in, captioned sketches to Harold Ross, the New Yorker’s editor, suggesting that the magazine publish them as cartoons. Ross said no — these sketches were too amateurishly drawn, too odd, and too disturbing. White persisted, however, and Ross finally relented.

The first drawings by Thurber appeared in the magazine in 1930. They were of a dog (either dead or in a trance) and a seal that disappointed its owner by showing no interest in balancing a ball on its nose. They illustrated a short facetious advice column for people who were baffled by their pets. Thurber began to take his sketches seriously, and from then on a “Thurber cartoon” was a regular and deeply relished feature of the magazine.

But this post is about “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”. I am discussing Thurber’s drawings in this post because they, along with “Mitty” (and the stories in My Life and Hard Times) seem to me to be Thurber’s masterpieces. The cartoons and this story express with economy and brilliant originality the bafflement and embarrassment and fears of ordinary men snd women who do not welcome the irrational into their lives but there it is.

Chances are good that you know, more or less, what “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” is all about, and chances are equally good that you’ve never read it or haven’t read it for a long time. Read it now, for its economy, its matchless construction, its pathos, and its humor.

Thurber is a minor writer. He does not probe the human soul as deeply as his literary hero Marcel Proust, nor does he marshal the particulars of character and circumstance as well as his greatest hero, Henry James. And so what if he wasn’t Proust or James? He was Thurber!

Superior comedy tied to misery — there it is again. It’s hard to find comedy that’s not somehow linked to sadness or anger or cruelty, and maybe that’s the point. Humor is one of the things that helps us deal with insanity, internal and external. I don’t know enough about Thurber to understand the true nature of his inner turmoil, but tales such as “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty”, “A Couple of Hamburgers”, and “The Catbird Seat” rise to a wonderful homage to the human comedy.

LikeLike

As he wrote, in the end, the claw of the sea puss gets us all.

LikeLike